Stonecutters Urban Ecology 101: Urban Therapy

Joseph Conrad

Special Contributor (hover over photos for descriptions)

Living and walking about a city is always an exciting experience for me as a stone history buff: something new is around every corner.

Living and walking about a city is always an exciting experience for me as a stone history buff: something new is around every corner.

It’s like a road cut for a geologist or a walk in the forest for an ecologist. Up to now, Chicago has been my favorite city, although my son says New York City is better.

I have a simple 4-step program that may help you enjoy your urban walks as well. It’s an urban ecology starter that works for me.

I have a simple 4-step program that may help you enjoy your urban walks as well. It’s an urban ecology starter that works for me.

I believe there have been four major changes in the stone industry since 1850, which have helped define the urban landscape–which I call “Footprints in Stone.”

I believe there have been four major changes in the stone industry since 1850, which have helped define the urban landscape–which I call “Footprints in Stone.”

Recognizing them helps me put urban forms into a time frame, but it is not perfect. There is overlap and digression, just as there is in fashion. But it’s a useful historical reference system, and a sense of history never hurts; it should help to make one more comfortable in our urban environment.

Recognizing them helps me put urban forms into a time frame, but it is not perfect. There is overlap and digression, just as there is in fashion. But it’s a useful historical reference system, and a sense of history never hurts; it should help to make one more comfortable in our urban environment.

1 - Local Stone on Stone 1850-1910

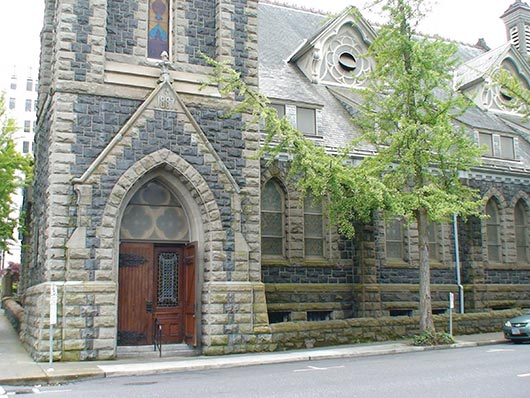

In this era, stone was locally quarried and cut by hand as I show in my “Lost Trade of Stonecutting” blog. It is a totally romantic period, before compressed air or useful gangsaws.

This technology certainly provided a sense of place to urban areas: cities defined by local geology. It’s the era of the vagabond stonecutter going from job to job, city to city. Many architects came out of stonecutter backgrounds at this time, since stone was the fundamental building material: cities reflecting the ground they are built on, giving rise to urban identities defined by stonework.

2 - Deep Drilled Hammer Face 1900-1930

This technology was developed with the invention of useful compressed-air. It often used local stone as well, if good building stone was available. However, if there was no local stone suitable for architectural construction, regional granite was often used. Softer stones like limestone and sandstone would still often be cut by hand locally. Stone was removed from quarries by drilling and blasting horizontal beds and drilling vertical blocks to mill-block sizes. Slabs were split off to be hammer finished flat with multiple air hammers called Drifters. This was the era when stone cutting was infamous for dust-born ailments we call silicosis, most often caused by pounding the stone with air hammers to shape.

This was the era when my father and his three brothers first started in the stone trade. Faces of buildings became smooth, not polished with beautiful details. Columns were cut on lathes, flutes often cut by hand with hand-held hammering tools. Intricate details including relief sculpture were put into building façades in granite as well as sandstone and limestone. Stonecutters were employed at job sites as well as quarry fabrication sites. Slowly, the cutting and shaping of stone went from local to regional fabrication facilities with sophisticated and stone resources. Beautiful permanent stone-on-stone buildings were created. Many of these buildings have been gutted out and refitted, and still serve as great urban architecture for us to enjoy.

3 - Polished Smooth Face 1925-1970

The next stone building type totally challenged the relationship between the local stone economy, and both people and local stone identity. The industry separated local knowledge about stone resources and set the stage for building façades for the first time. Stone was no longer cut or quarried locally. Stone was no longer a structural building component, but rather it became a veneer over a concrete structure.

The modern Gangsaw made low-cost fabrication of two-inch and thicker slabs, or what we call dimension stone, possible. Huge surface grinders brought stone slabs to a high finish. Then they were sawn to size and sent to local building sites to cover concrete as decorative and protective veneers. This new building process, the modern high-rise, elevator-equipped building became covered in stone, terra cotta, or brick, all as veneers.

These production facilities were not placed locally, but rather close to the source of large quantities of quality stone quarries, varieties of color being an important factor. The stone blocks were shipped by rail to the centrally-located modern fabrication plants; there, stone fabrication expertise flourished. Finished cut-to-size building skins were then sent to local job sites for a new trade called “Stone Setters” to install. Thus, we now have the separation of local knowledge, its origin and how it is fabricated.

This all happened in my father’s and my lifetime.

4 - International Thin Cut Stone 1970-Present

The final stone footprint once again came with a breakthrough in mass gangsaw cutting. This came about with the ability to mass-cut thin slabs by putting post tension in diamond or shot gangsaw blades. Fast mass-production of multiple slabs brought costs of stone down for building construction and made stone slab prices such that the general public could afford stone countertops for the first time. Suddenly there was a stone revolution all over the world!

I believe this technology started in Germany and Italy. Even today, if you go to the Italian stone fabrication centers at the base of the Apennines, you will see thousands of blocks of stone drilled out from quarries all over the world to be sawn with these gangsaws–although North and South American and Asian facilities are catching up by using this technology.

But the important point for the urban walker is that once again, stone is used as an integral part of the building structure. Steel skeletons are erected with floors floating free of concrete or sidewalls. Their weight is transferred down by use of vertical steel supports. What is called “Curtain Walls”–a very descriptive term of glass and stone –are mounted on horizontal frames with their mass also transferred to vertical steel supports. Thus, the glass and stone skins become the protective skin of the structure. Stone is once again a useful and important structural component of the building. This makes curtain walls a practical and economical building component, not just a pretty face covering concrete. Economical mass production of stone slabs certainly has changed the urban landscape.

This is the current state of high-rise construction. Thankfully, design professionals soften the building by employing historical stone elements to add detail to this harsh building system. I call them urban furniture. Sculpture is used as well. It would be a pretty bleak world if curtain wall construction was not offset this way; of course, traditional tricks of texture and color soften these structures as well.

Joseph Conrad has worked and played in the stone industry for fifty years, from architectural drafting to quarrying to stone installations to founding a stone fabrication business to stone exploring and eventually to sculpture.

His blog shares his lifetime of experience. It is meant to make the urban landscape understandable to everyone. He hopes to help provide a sense of place in the urban environment by providing his insights on stone history & fabrication. He is the founder of Conrad Stonecutter in Portland, Oregon (http://www.conradstonecutter.com).