Thermal Forming Quartz Slabs for Fun and Profit

Brian Brutting

Photos by Brian Brutting

Bending stone was once thought to be impossible, except for the thinnest veneers. With the advancement of engineered quartz came some creative ideas in bending hard surfaces.

|

|

Above, left: Milling reduces the thickness to between 1/4 and 1/8-inch. The tighter the curve, the thinner the work piece will need to be. Above, right: A standard turkey fryer will work just fine to boil water. The goal is to raise the core temperature of the milled slab. The water needs to be boiling to make sure it doesn’t cool too much in transfering from the pot and pouring on the work piece. This is a job for three workers: one to pour, and two to evenly bend the piece, and tighten the clamps. |

Since engineered quartz is made with up to 10 percent resin, it is possible to manipulate the material much like solid surface fabricators did back in the day. The highest quality engineered quartz is still 90 percent real stone content, which is very important to successfully bend a slab of engineered stone.

Note that the process can be tricky and is not covered under any manufacturer’s warranty, so it strictly creative. Never the less, I see tons on specification for thermal formed pieces all the time, and some of the very best fabricators get the lion’s share of this very lucrative work.

The process really is not complicated – just time consuming – and it sometimes takes a little trial and error to achieve the best results.

All you need is the ability to mill material, a large source of hot water, clamps and a wooden form to bend your shape.

Not all colors of engineered quartz can be formed, though — only material with very tight quartz grains. For Caesarstone products, this includes the 2,000, 4,000 and 5,000 series slabs.

It is important to note you cannot use material with glass content in it. If you are not sure, check the manufacturer’s content specs. Engineered quartz containing glass (including recycled glass products) will shatter under the bending process — a potential dangerous situation.

The hot water source can be a simple as three or four turkey fryers boiling water, or as complicated as a custom bath. As long as you can boil water it will work. You will also need a laser thermometer to check the water temperature.

Safety should always come first. Make sure to work in a well-ventilated area, with good drainage. Wear protective gear at all times. Heat resistant gloves and eye protection are a must; boots and shop aprons are optional.

In constructing custom bend projects, I always find a box joint is better than a miter joint for this type of application. It gives you a little more wiggle room to produce tighter seams. I just overcut the top part of the joint, extend the top flange, and shape after limiting the pieces.

Wooden forms to bend and clamp material to are important for the process. If you’re not able to make your own, most mill workers can for a fee. The photos below show a well-designed custom form made by a milling shop, shown in use during the bending process. It slots together, with cut-outs built in for places to securely to clamp the piece being shaped. Strap clamps will also work for the clamping process. Once the piece has cooled and set you need to immediately glue or build into your final shape.

Why learn to thermal form? It is hard enough to make a profit in the stone business. The math is simple: you can make ten times more on custom shaped jobs than on other projects. Visit www.youtube.com/watch?v=je3-CSw_W5c for a demonstration of the process.

|

|

Above: Heating, bending and clamping in process, and completed. Allow two to three hours for the piece to set and cool – longer in hot and humid conditions. Leave clamped until ready to use. Once unclamped, the resin in the material will start to revert to its original flat shape. |

|

|

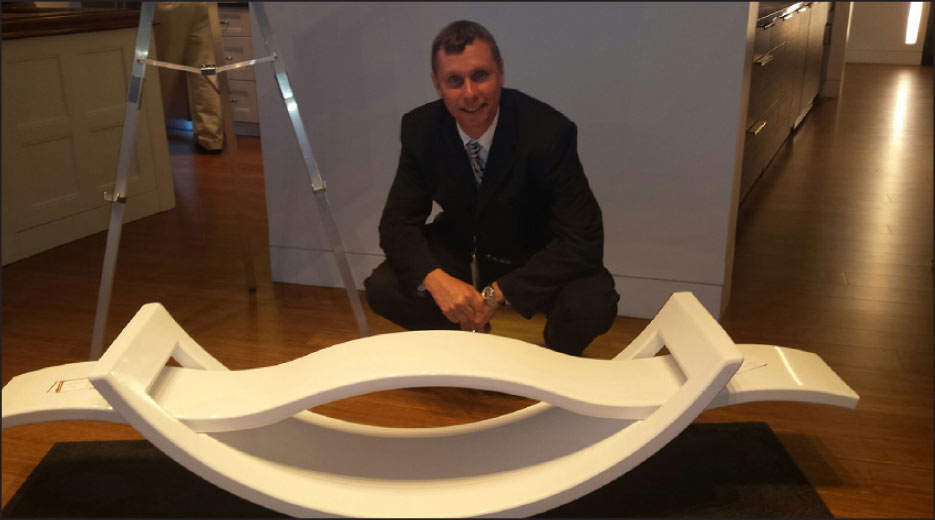

Above: Bending a piece prior to building with box seams. The finished piece is a see-saw, built for a competition. |

|

|

Above: Custom-shaped top constructed with box seams. The excess material is removed with a grinder. |

|

|

Above: Brutting and a box-built see-saw. |