Living and Working with Stone: Maine Artist Mark Herrington

Peter J. Marcucci

Photos Courtesy Mark Herrington and Peter Marcucci

|

|

Above: Herrington’s Recurrent Journey dates from the 2009 Scoodic Symposium, now placed in the Franklin Granite Park, Franklin, Maine. |

|

|

Above: Herrington built his studio with large barn doors to accommodate his larger sculptures. |

It is not that often that I get to travel to my home state, Maine, for a story. This trip I had the pleasure of getting acquainted with Mark Herrington, a talented stone carver who has worked with stone to produce everything from countertops, to furniture, to sculpture.

While making my way through the towns of Ellsworth and Sullivan to Herrington’s shop and showroom in Franklin, Maine, it was obvious that this pristine area has a long history of stone quarries. Mark’s shop sits adjacent to an old quarry as well as a picturesque pond fed by a small waterfall – an idyllic spot to contemplate the next sculpture, fish for trout, or simply take a break from the daily grind.

Every nook and cranny of Herrington’s showroom is filled with original art, thoughtfully placed. From his collection of tools and machines, Mark and his rustic studio have gone through many changes, throughout the past 20 years. This is his story.

The Metamorphic Years

“I Grew up in Orono, Maine, and in 1979, at the age of eighteen and right out of school I started building guitars,” recalled Mark. “At the time, I just wanted to build things, and later on got a job in Boston making harpsichords. I did that for a while until 1980, when I mostly bounced around in the Portland, Maine area doing cabinet work, gaining skills and staying poor. Then, in 1982, my dad called me and my brother on the phone saying, ‘Come on, let’s build a camp,’ and five years later we’ve got this huge house. It was all part of his diabolical plan, and we now called it home and moved in with him in Gouldsboro, Maine.”

By the late 1980s, Mark wound up building houses on Mount Desert Island. They were big custom mansions for millionaires with lots of woodwork. He ran the woodshop and built cabinets, and that’s where he met Jeff Gammelin, the owner of Freshwater Stone in Orland, Maine.

“Jeff was putting stone countertops on the cabinets I built, and we would talk about them and work together on designing the next countertops. Jeff also said that if I ever wanted to work in the stone business, to come and see him for a job.”

As time passed, Mark bought the property to build his current location. “My shop and showroom is right next to the Orcutt Granite Quarry, which is part of the Sullivan shield. The towns of Sullivan and Franklin are very old granite quarry towns, and the quarry was opened in 1889 to produce cobbles for Haverhill, Massachusetts.

“As I was finishing up with the last piece of plywood for the roof and getting ready to set up my shop to do woodworking, I was looking out over the quarry thinking, I’d rather be working with granite than wood. So I went over to Freshwater Stone and asked Jeff if he still wanted to give me a job, and he hired me. I had never worked a piece of stone until I worked there, but I knew how to measure from doing cabinets, and started selling window sills and framing. I worked there for four years until 1993, and then wound up coming back here and opening up my own little stone countertop shop. I did my own templating and did cutting with a hand saw, while part-time guys would help me polish and install. It was great, but it wore me out. At the time, I wasn’t selling that many countertops to walk-in customers. It was mostly to kitchen and bath shops where I put in displays.”

During the mid 1990s, while still fabricating countertops, Mark had begun doing sculpture work for himself and getting a little more creative. He also wanted to get back to doing furniture design, and began wondering how to marry big pieces of stone to big pieces of wood. It wasn’t that easy, he explained.

“By 2005, I was getting very exhausted by the level of work I was doing, and realized I could do one of two things. I could go full bore on the countertops and do really well, or scale back and feed my creative side. I chose the latter, and it was an evolution from 2004 to 2007. Part of it was just getting the confidence that I could at least make a living, and decided that I was going to do both artwork and countertops, at least for a while. I figured that if I could do just one countertop job per month, I could pay all of my expenses and work on my art, but it was really hard scaling back, because it’s hard to say no to the clients I’d had for years.”

As it turned out, while Mark was in the process of scaling back his client list and getting down to one countertop job a month, it’s also when the financial crash came and began doing the culling for him. “This area being on the fringe, the work died, and I did not do another countertop for a year after that.

“At the time, I just figured that I’m now on the accelerated plan of dropping my clients, and by the time they started coming back, it was easy to say no. Moreover, I was having some success making and selling my art around 2011, and realized that this is truly what I want to do, regardless of how much money I make doing countertops.”

|

|

Herrington’s studio is located by the historic Orcutt granite quarry, which opened in 1889. |

|

|

|

Herrington at work at the 2017 Boothbay Symposium. This biannual symposium brings together Maine artists and an international guest to work in Maine granite every other summer. |

Material is Just a Stone’s Throw Away

Having grown up in Maine, Mark’s father was an avid outdoorsman, and almost every weekend they would be hunting or fishing somewhere. “I was always out amongst stones and nature, and loved those rocky places on the streams where the big trout holes are. It’s also when I fell into the idea of using local glacial erratics, because they were available right here. (Editor’s note: A glacial erratic is a rock that differs in size and type from what is native to an area.) Glacial erratics actually became my entry in to form, so that as soon as I picked up the canvas (the stone), it wasn’t blank. Once I started getting into that, it all started coming along pretty easily, and then it was just a matter of bringing in a slightly more aesthetic vocabulary. I like using Basalts, because I like the color contrast of the polish on the skin, particularly when I get them from the local gravel pit, because it goes orange due to the oxide. Whereas, if I get them on the beach, it’s more like slate, and cleaned.

”I also started getting into colors and that’s kind of where I am now. I spend a lot of time scouting for materials that are interesting. There is the outer form of the stone, the inner mineral form of the stone – what it will look like when it is processed – and there is the form of the shape that I impose on it. Trying to balance all of those is very interesting.”

Franklin and Sullivan are not only granite towns, but also have a bunch of gravel pits. Ninety percent of the sculpture in Mark’s showroom came from these pits, from stones that had washed down river from Baxter State Park. “When you go in to these pits after a rain, it looks like a gumball machine,” explained Mark. “It’s really cool. We also have Ellsworth schist here that is really nice. I do like working with marble, but I cannot afford it, and local granite is not that hard. But my favorite stone is always the one I’m working with at the time. Sometimes I’ll pick a stone thinking that it’s one thing, and it winds up being chert. Chert is really hard, it doesn’t like diamonds, and it takes twice as long to carve as basalt, a stone that diamonds do love. I don’t use anything from my own quarry. It’s much easier for me to just go over to my friend Conrad Smith, who operates the Sullivan Granite Company, and buy stone from him. The quarry is right across the bay.”

When needed, Mark also makes money during the summer doing drywall and masonry work (walls, chimneys, fireplaces, walkways) with a friend in Bar Harbor to make up for the slow times from mid October to June.

|

|

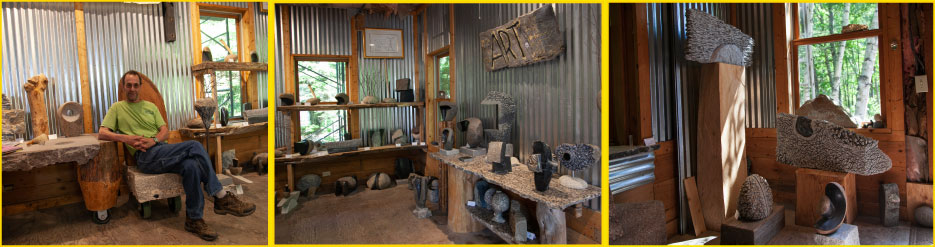

Above, left: Herrington, seated on one of his hand-made chairs in the gallery section of his studio, which includes rustic, functional furniture as well as smaller, more detailed stone and wood sculptures. Above, middle and right: There are usually well over 100 pieces on display. “My studio and gallery are open to the public by appointment or chance,” says Mark. |

The Schoodic Symposium Years

|

|

Herrington often has multiple works in progress in his studio. “I love to share how I do things – the tools I use, and helpful hints for how to do some things yourself, if you’re interested in working with stone.” |

“I was an assistant in the first Schoodic International Sculpture Symposium (SISS) in 2007 for my friend Don Meserve. Don had just had lung surgery, and I was assisting him to make sure that he didn’t get too exhausted. It was at the time when I was making the transition from countertops to art and design. Later, as one of the featured artists, I was in the second SISS in 2009. Funny, I’d say ‘symposium’ and people didn’t know what I was talking about. They thought it was like a scientific symposium where people get together and chat.

“The Littlefield Gallery in Winter Harbor, Maine opened around 2008, and they came and saw the 2009 symposium, and decided that stone sculpture was going to be one of their focuses, because there are so many Maine sculptors. They also liked this type of art, which helps to give us a market. Stone sculpture is a tough impulse buy, and I think one of the reasons is because it is carved and not impulsive. It is a material that says permanence, and that’s what it’s all about.

“We’ve also had stone symposiums at J.C. Stone in Jefferson, Maine; Viles Arboretum in Augusta, Maine, and one in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. These symposiums are interesting because they are not for public work. You don’t get paid for doing it, but you also need to cover your travel, tool and food expenses.

J. C. Stone offers free materials to all the artists for this event, and the artists own their artwork, and can sell it afterwards, if they want.

“I’ve done pretty well in selling most of mine. I show at three Maine art galleries. The Littlefield Gallery in Winter Haven; Gleason’s Fine Art in Boothbay, and June Lacombe’s gallery in Pownal.”

“When I started doing art, I knew it was going to be a long-term thing, and when I looked at the other artists who had made it, they did so because they stuck with it, and this is what I’ve done. Winter is a great time to sculpt in this shop. The light is good, it’s quiet and there are no tourists, so I can get huge amounts done.”

“Right now I’m trying to figure out a design for a charging table where all the electronics of the household can go with all the cords and everything. It’s utilitarian art, because I see the utility. I’m not really sure what it will look like or where it will lead to, but that’s designing, which solves a problem, unlike art, that doesn’t solve any problems at all except aesthetically. I’m also working on a fountain that makes a rain pattern, not a spray. I’m not there yet, but I do have a mockup.

“Luckily, these last couple of years, I haven’t had to do any side jobs and have only done artwork, so to those looking to begin creating art I say this: To excel, you’ve got to be thick-skinned and stubborn. People will say the darnedest things about your work, and your motivation has to really come from inside. You have to be able to push through criticism and try to keep your self-doubt down, because if someone says something negative, you can’t lose your motivation. Art comes from the inside and you put it out there afterwards, and you do get better. Don’t do big things at first, just small things, and just do it!”

For more information about Mark Herrington visit www.markherrington.com/the-studio .