Bluestones: Rivers and Deltas Create a Versatile American Sandstone

Karin Kirk

usenaturalstone.com

usenaturalstone.com

Photos by John Malyshko, Courtesy Natural Stone Resources, Inc.

Bluestone. It’s blue. It’s a stone. End of story, right? Oh no, dear reader, you won’t get off the hook that easily. There’s a lot more to bluestone than its refined good looks. Did you know that bluestone only comes from one region? And that it’s the remnants of a mountain range that doesn’t even exist anymore? And that it can be all kinds of colors? If there’s one thing that’s always true with natural stone, it’s that there’s more to these rocks than meets the eye. Read on to learn why bluestone is a unique American stone that’s as useful as it is beautiful.

Bluestone is Not Just Blue

Bluestone is a fine-grained sandstone from Pennsylvania and New York, characterized by its grey-blue color—but it’s not always blue. “There are so many color variations,” explained Bill Mirch, Vice President of Tompkins Bluestone. “Light blue, grey, green, brown, lilac…” Mirch ticked down the list of colors expressed in bluestone. “There are a lot of nice choices.”

Ancient rivers gave birth to bluestone, and this sandstone is the result of a region-wide river system. As with all sedimentary rocks, the particulars of the stone reveal details about its formation. For example, the different colors tell us if the stone was exposed to oxygen during or after its formation. Orange, red, or brown colors are caused by an oxygen-rich environment. Green, turquoise, or blue tones are a result of oxygen-poor conditions, which can occur when decaying organic matter in the sediment uses up all of the available oxygen.

A variety of different ingredients make up bluestone: feldspar, quartz, mica, clays, and rock fragments. In geologic terms, this stone is called a greywacke (pronounced “gray whacky”), which is a sandstone made of a mixture of different particles. Furthermore, ‘greywacke’ is yet another example of how geology is rich with unusual/ridiculous vocabulary terms!

But this jumble of ingredients tells us something about bluestone. As sediments are transported farther from their source, they sort themselves out into similar minerals of similar sizes. But bluestone, being made of a diverse mix of ingredients, is made up of sediment that traveled a relatively short distance down a river. It also hints at the fact that all bluestones are not identical. The range in colors, layering, and texture is one of bluestone’s best assets.

Bluestones are the Remnants of an Ancient Mountain Range

Let’s do a little time travel back to the Devonian Period, nearly 400 million years ago. A mountain range, called the Acadian Mountains, was being uplifted along the east coast of North America. As a tectonic collision cranked the mountains upward, erosion sought to wear them back down. Rivers carved out valleys and carried away the sediment.

Let’s do a little time travel back to the Devonian Period, nearly 400 million years ago. A mountain range, called the Acadian Mountains, was being uplifted along the east coast of North America. As a tectonic collision cranked the mountains upward, erosion sought to wear them back down. Rivers carved out valleys and carried away the sediment.

At the foothills of the mountains, the rivers met an inland sea, the currents slowed, and the rivers laid down blankets of sand, gravel, and clay. More sediment piled on top of that, and the pressure from the overlying layers helped glue the particles together to create solid rock.

A huge range of rocks got deposited in this manner, and all together they are called the Catskill Delta Formation. This deposit is up to 10,000 feet thick, and covers parts of eastern Pennsylvania and southern New York. The Catskill Formation includes black shales, thick beds of coarse red sandstone, occasional limestones, and lenses of bluestone. The bluestones were formed from sandy deposits in river channels and river banks. Layers of shale and siltstone are usually found above and below the bluestone layers.

Bluestone was not laid down in a continuous blanket. Instead, rivers and deltas left behind pockets of sand. As rivers shifted across the landscape, the sandy layers did, too. As a result, bluestones are found in small, discontinuous layers scattered throughout the region.

It’s amazing to think that the Acadian Mountains that shed their sediments to create the Catskill Formation no longer exist at all. They’ve been erased by erosion and overridden by the Appalachian Mountains, which formed in a similar way, about 50 million years after the Catskill Delta. The Appalachians, of course, are still with us today, but at some point they’ll lose the battle with erosion too, and will be worn away by restless rivers.

|

|

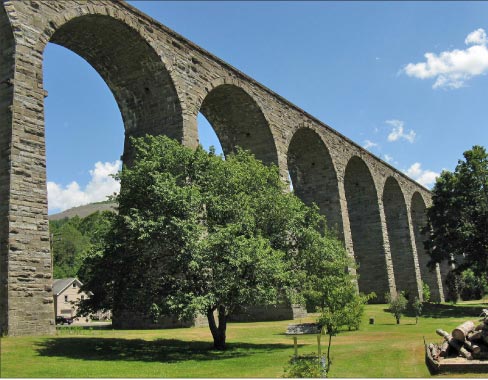

The Starrucca Viaduct railroad bridge in Lanesboro, Pennsylvania was built in 1848 with Ashlar Bluestone, quarried near the site. This massive stonework bridge marching across the landscape is still in use, a beautiful and functional example of this durable American sandstone. Photo: Robert Theobald, HistoricBridges.org |

Geologic Variability Leads to a Versatile Stone

The geologic origins of bluestone conspired to create a particularly useful material. The sand grains of bluestone have been tightly cemented together, yielding a strong and durable stone. It has a consistent texture that can be left as-is, or can be worked into a variety of different finishes.

Bluestone’s natural layering allows the stone to be cleaved into agreeable flat shapes, and variations in the thickness of the natural layers provides a range of stone for different uses, from chunky blocks to thin sheets.

The way that bluestone was deposited in individual layers and pockets gave rise to small quarries scattered throughout eastern Pennsylvania and southern New York. The small scale of the operations favored close-knit crews working by hand rather than with heavy machinery. “Information was handed down from generation to generation,” explained Mirch. “It was a family thing.”

Because bluestone layers fade in and out across the landscape, quarrying it “is really an art,” said Mirch. In some places the sandstone beds are thick, which are useful for stair treads, curbing, and sills. Thinner layers are well-suited for paving or patio stone. Broad slabs are ideal for sidewalks. Because of the variability, “it’s harder to understand how to extract it,” offered John Malyshko, owner of Natural Stone Resources, Inc., but the upside is that, “different products come from different parts of the formation.”

“The Precursor to Concrete”

Bluestone has been a useful stone since the 1800s, when it began to be quarried for curbs, sidewalks, door sills, window sills, and paving stones. Much of the stone was shipped to nearby New York City, where “it was the precursor to the concrete sidewalk,” said Malyshko. “You can still see 200-year-old bluestone steps and paving material.”

A spectacular example of early bluestone construction is the Starrucca Viaduct, a 1,000-foot- long, stone railroad bridge in Lanesboro, PA. The viaduct was built of Ashlar bluestone in 1848, and was completed in only a year, thanks in part to the fact that the quarry was just three miles from the viaduct. If you had any doubts about the strength and durability of bluestone, take a look at that structure and appreciate that it’s still being used for commercial rail freight today.

Many Uses for Bluestone

Many Uses for Bluestone

Today, bluestone remains a popular choice and is one of the most abundant American natural stones. Patios, stair treads, stone walls, and pool coping are common uses of bluestone. In part, bluestone remains in demand because of its versatility. Daniel Wood, natural stone consultant for Lurvey Supply and chair of the Natural Stone Institute’s education committee, described the many facets of bluestone. “You can work it and craft it. You can have different sizes, different surface textures. It can be layered or not.”

The natural layers of bluestone can be “cleft,” or broken apart, yielding a naturally flat surface with just a hint of texture. In the early days of bluestone, its tendency to break along flat layers was part of its appeal.

But now, Mirch explained, diamond-blade saws have transformed the industry and ushered in myriad new uses for bluestone. No longer reliant on natural layers, stone cutters can saw the stone into specific sizes and thicknesses for architectural use, and mill it into thin tiles. “We’ve expanded our market to the [home’s] interior,” said Mirch.

Different finishes can mesh with different parts of a home. Bluestone can be tumbled to give it an antique look, it can be brushed or honed for smooth floor tile, or a ‘flamed’ finish can be applied, which leaves a planar surface with a slightly rough texture. Mirch summed up bluestone’s adaptability: “It goes from rustic to contemporary, very easily.”

Using the same stone in different ways can unite different parts of a project. “There’s a rhythm; a simplicity of materials,” said Wood. “It ties together into a cohesive design.”

Even bluestone’s leftovers are useful. Thinner layers can be made into tile, and crushed bluestone can be used as gravel. “There’s so many things you can do with it, or to it,” remarked Wood.

‘The Industry is Thriving’

‘The Industry is Thriving’

Even though the bluestone industry is made up of small and medium-sized quarries, the stone has a huge reach. Demand for bluestone is highest in the northeast. “It fits the vernacular of the region,” Wood said.

But bluestone is shipped far and wide. “It’s very popular, nationwide,” explained Malyshko. “It’s like bread or butter. People know the material. It’s a safe choice.”

“The industry is thriving. The quarries are doing great,” observed Wood. “They can’t make it fast enough.”

Malyshko echoed this sentiment: “Every block that’s extracted is sold.” Mirch added, “We never have a surplus. Ever.”

For example, Tompkins bluestone supplies 6,000 to 8,000 square feet of bluestone sidewalks for historical neighborhoods in New York City every year. Mirch appreciates the continued use of traditional natural stone. “I really can’t get jazzed over a concrete sidewalk,” he quipped.

Furthermore, this American stone fosters American jobs, and not just in the quarry: “Trucking, machining, diamonds, blades…” Malyshko counted off the ways that bluestone stokes the local economy.

Perhaps bluestone is the quintessential American success story.

A geologic remnant became a useful product, and small-scale quarrying fostered a bustling industry. Over time, quarriers, masons, and architects innovated new ways to use this old stone. And all the while, customers have flocked to it, keeping the industry vibrant and allowing the cycle to continue. Bluestone’s easygoing versatility shows us that sometimes the simplest ideas are the most durable.

Karin Kirk is a geologist and science educator with over 20 years of experience. She has taught college level geology, online courses and organized field trips. She currently works as a freelance science writer and education consultant. She brings with her a different perspective to the stone industry. Karin was an education program presenter at TISE 2018 and a regular contributor to usenaturalstone.com and the Slippery Rock Gazette.