Limestone — A Tropical Seabed Brings Us a Practical Stone

Karin Kirk

usenaturalstone.com

Travel with me, if you will, to the Mississippian Period, 330 million years ago. A vast, tropical sea occupied most of the U.S. The weather was warm, even hot, due to the fact that North America was parked over the equator, far south from our present, somewhat chilly location.

The water was warm, crystal clear, and not too deep. The sea teemed with life: coral-like bryozoans fanned in the currents, snails grazed along the sea floor, and sharks patrolled the waters. The sediment at the bottom of the sea was a mixture of shell fragments and lime mud, with gentle waves rolling limestone pellets into rounded grains. Sounds kind of nice, doesn’t it?

This inland sea left behind a blanket of limestone hundreds to thousands of feet thick. Mississippian-age limestones cover huge swaths of the U.S., creating famous building stones in Indiana, caves in Kentucky, the prominent Redwall Limestone in the Grand Canyon, and the familiar Madison Limestone cliffs throughout the mountains of western Montana.

So, next time you come face-to-face with a limestone slab in a showroom, pause and indulge yourself with a little mental time travel to the prehistoric, balmy ocean that created this stone.

|

|

A dramatic backdrop for the Empire limestone quarry in Indiana. |

|

|

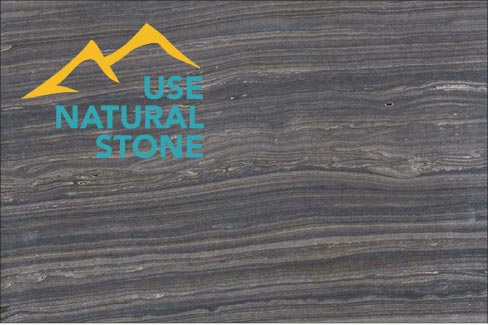

Above: Eramosa limestone: lovely, uniform layers with ripples, like a cross-section of seabed – which it is. |

|

|

Above: Fossil in the limestone floor at the Vermont Statehouse. |

|

|

Above: Seagrass limestone is quarried from a bedrock quarry in Eflani, Karabük, Turkey. This sedimentary stone was formed on shallow sea beds from Monsoonal rains washing minerals, plants and animals into the sea. It is composed mainly of calcite calcium carbonate. Structurally, Seagrass is a very hard limestone. Some common characteristics visible in this limestone are quartz veins, grey portions and many fossilized shells in each piece. Photo courtesy Arizona Tile |

|

|

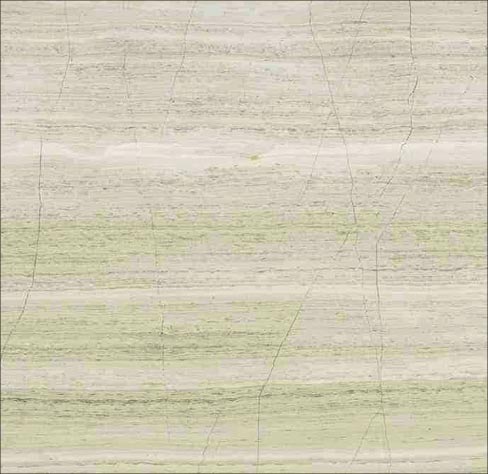

Above: Silver Beige vein cut limestone. Photo courtesy Arizona Tile |

|

|

Above: Indiana Limestone Company, quarry face. |

|

|

Above: The Biltmore estate mansion in North Carolina is perhaps the most famous private residence in America. It was constructed with Indiana Limestone from the Dark Hollow quarry near Oolitic, Indiana. |

A Practical Building Stone

Quarries throughout the Midwest have been making use of the Mississippian seabed for nearly 200 years. Skyscrapers, universities, and city buildings from coast to coast are clad in limestone, primarily quarried from Lawrence, Monroe, and Owen counties in Indiana. There, a 60-foot thick layer of Salem Limestone produces a uniform, non-layered, grey stone with a smattering of fossils.

Salem limestone is used in all 50 states, on buildings as utilitarian as post offices, as soaring at the Empire State Building, and as robust as the Pentagon. Look around your own city and see if you can spot some Salem Limestone. It’s far from flashy, and at first it looks a lot like concrete. But sidle up and look close, and you’ll see fossil fragments. Be warned though, that people will think you’re a little nuts when they watch you press your nose up to the post office!

Thanks to our former inland seas, the US is home to many limestone quarries, generally arranged in a north to south band through the country’s midsection. (The Mississippian Period is named because these rocks are plentiful in the Mississippi River valley.) Texas, Kansas, Indiana, Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin all produce architectural limestone, satisfying a need for locally derived, native stone that has not traveled halfway around the globe.

Limestone Forms in Tropical Seas

Most limestones form in the same basic way. They are made of shells, fragments of corals and similar creatures, and the teeny tiny shells from plankton. All of this stuff is made from calcite – calcium carbonate – an abundant mineral in geology. When the marine creatures die, their shells drift to the sea floor. Sometimes currents and waves grind the shells into pieces. Other times, the shells dissolve into the seawater for a while, before settling out as very fine lime mud. In either case, the sediments pile up in layers and eventually get compressed enough to form solid stone. If you look close at a few different limestones you can usually recognize some of the common ingredients:

Shell and fossil fragments, which look like whole shells, parts of shells, or bits of other interesting shapes.

Limestone pellets, (called oolitic limestone) which look like sand grains, but are made out of calcite instead of quartz sand.

Crystalline limestone fills in the spaces between the other ingredients.

Fine-grained limestone, these smooth-looking stones don’t have visible fragments. Typically, these are formed in deeper parts of the sea where the currents are sluggish.

Limestone is not just an artifact of ancient seas. It forms today in places like the Florida Keys and the Bahamas. Enticing images of tropical beaches show milky-hued, blue-green seawater; the light color is from calcite dissolved in the ocean water. Eventually, that will settle to the sea floor and make a new layer of limestone.

Meet Limestone’s Cousin – Dolomite

Dolomite is a variation of limestone that has a slight chemical difference. While limestone is made of calcium carbonate, dolomite is calcium-magnesium carbonate. Dolomite does not etch quite as readily (it takes a few minutes instead of happening immediately) and is a teeny bit harder. Essentially though, limestone and dolomite are basically interchangeable.

Limestone Colors Are Soft and Uniform

While all limestones form similarly, the stone can take on a range of colors and patterns. You’ll find limestone that’s tan, pale yellow, pink, deep red, gold, grey, brown, or black. The stone can have a uniform color, like Texas Pearl and Belgian Blue, or patterned with bold veins, like Grigio Carnico.

Pink, buff, and light yellow limestones evoke a tropical, beach-house look, which is fitting considering the origins of the stone. Limestones quarried in Texas such as Desert Sunset and Cedar Hill Cream can fit the bill when seeking a natural stone in a bright, sunny color.

But limestone is versatile. The even tone, lack of speckles, and quiet patterns offer a sleek aesthetic that can be hard to find in natural stone. Pietra Cardoso or Silver Beige Vein Cut are two examples of limestones that could play well in contemporary designs.

Textures, and Layers, and Fossils, Oh My!

Just like people, some limestones lead a more complicated life than others. Limestones that have the misfortune of living near a fault are subjected to stresses that cause the stone to fracture in place. Calcite carried by groundwater glues the pieces back together, and the rock slowly fixes itself. This whole process happens underground, and the resulting rock is still strong and usable, and is especially beautiful. The geologic term for this is breccia, which is reflected in names like Breccia Paradiso and Breccia Oniciata.

Some limestones have layers; some don’t. The layering reflects the currents and tides of the ocean where it formed. Layered limestones can have an architectural look to them, like the Eramosa Limestone (read more about this and other striped stones). Limestones without layers are better for the large blocks that are used in buildings, sculptural works, and monuments. The non-layered quality of the Salem limestone is one of the reasons it’s so widely used.

Perhaps the most exciting types of limestones are the ones with unmistakable evidence of their origins: fossils! Some slabs, like Sea Grass, offer a cornucopia of shells and shell fragments, like you’d find under your toes as you stroll along the beach. Other slabs might have a lone fossil or two, seemingly adrift in a lonely ocean. But by far the best is Fossil Black limestone, featuring an army of fossil nautiloids that look like they’re swimming in formation. Mounting this stone vertically gives the illusion of the sea creatures swimming in the ocean, rather than lying on the ocean floor (which, sadly, is how the stone actually formed). But hey, forget the somber reality and celebrate the vivid picture of these ancient squid-like creatures, zipping through the water with jet propulsion.

It’s worth noting that Fossil Black (sometimes called Black Fossil, just to keep you on your toes) is often classified as a marble, but it isn’t. Marble is a metamorphic version of limestone. The process of metamorphism wipes out the fossils. So if your slab has a fossil in it, it’s limestone, not marble.

Limestone: Properties and Uses

As with all stones, it’s best to match the natural properties of the stone with the way you intend to use it.

The most common architectural use of limestone today is in building stone and floor tile. Limestone also makes a beautiful backsplash, tabletop, or vanity. It can be used as a kitchen countertop, as long as you treat it gently, or you don’t mind a patina-type surface that reflects the real-world use that a countertop gets.

Limestone is made of calcite (as is marble, Travertine, and onyx). Its hardness is 3 on Mohs hardness scale, which means it’s softer than glass and knife blades, but harder than a fingernail. Calcite etches when in contact with commonly used acidic liquids, like pickle juice, vinegar, and your favorite red wine.

The porosity of limestones varies widely. Some have not been buried deeply nor compressed much. Others have been through the wringer and have been squeezed enough to make them dense. The porosity or absorption rate of limestones is sometimes listed in the specs for a stone. In all cases, limestone should be sealed to reduce the likelihood of staining.

A Natural Feel

A stroll through just about any Wisconsin and Minnesota neighborhood will feature limestone walls, paths, patios, or edging hewn from the popular Fond du Lac dolomitic limestone. The stone’s natural layers lend themselves to stacking or using as paving stones. The stone can be sawn into neat shapes or left in rough pieces, adapting itself to either a formal look or an easygoing, naturalized feel. DIYers can appreciate the Fond du Lac stone because it’s easy to work with and readily available. The widespread use of this native stone throughout the region helps unify the local landscaping and lends a sense of place.

Amid the glamorous, dramatic stones that grab our attention, there is something reassuring about limestone. Its local provenance and undemanding aesthetic offer a refreshing alternative; the reliable girl-next-door rather than the Instagram sensation. Limestone quietly does its job – as a building stone, garden edge, or tile – bringing a bit of the quiet, tropical sea into our everyday lives.

Karin Kirk is a geologist and science educator with over 20 years of experience. She has taught college level geology, online courses and organized field trips. She currently works as a freelance science writer and education consultant. She brings with her a different perspective to the stone industry. Karin was an education program presenter at TISE 2018 and is a regular contributor to usenaturalstone.com and the Slippery Rock Gazette.

|

|

Fond du Lac dolomitic limestone. Photo courtesy Buechel Stone. |