The Lost Trade of Stone Cutting

An Essay Describing Stone Construction Before Gang Saws or Compressed Air, 1800 to 1900

Joseph Conrad

Special Contributor

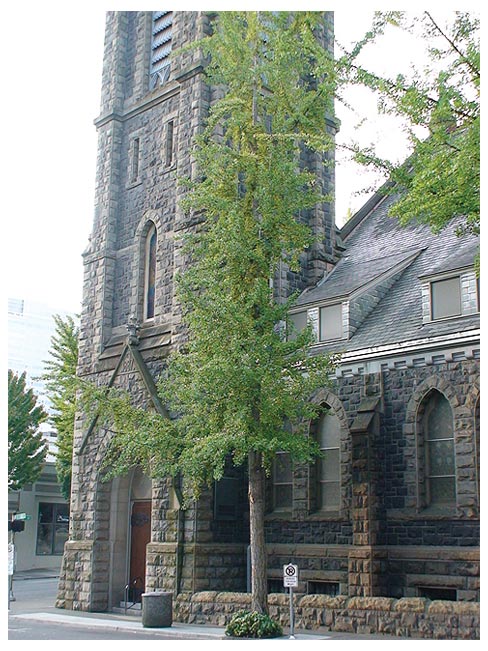

Have you ever thought about how those old stone churches, so much a part of Portland’s identity, were built? Walking with my father, the stonecutter, gave me an interesting insight back in 1965.

Have you ever thought about how those old stone churches, so much a part of Portland’s identity, were built? Walking with my father, the stonecutter, gave me an interesting insight back in 1965.

Thirty years ago when I was designing our company logo, I sketched a derrick lifting a mill block from a granite batholith and titled the company, “Joseph Conrad, Stonecutter,” doubting that anyone would understand what the logo was or what the title “stonecutter” means. The quarry and the trade had both been long forgotten.

Back in 1917, Portland had a significant stone cutting industry, with 17 to 20 companies that supported hundreds of people. The times and technology changed over the years. By 1980, about the time I was designing my company logo, Portland had only one stone company, which probably supported 10 to 15 people.

Styles and tastes changed, and today, Portland may have around 30 stone companies supporting perhaps 500 people. But during these changes much has been lost, for few of the people in the current stone industry have any sense of history or an interest in stones other than as a means to make a living— although all of them demonstrate a healthy sense of romance towards stone, since that is an integral part of the stone business.

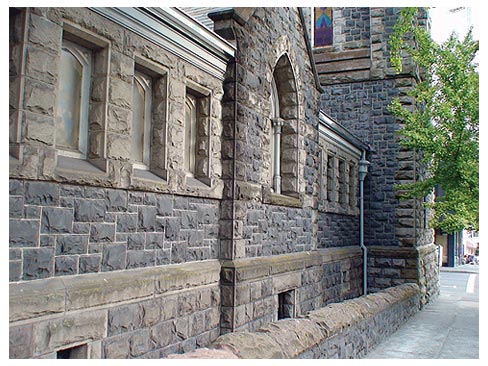

People who work with stone can leave permanent marks on the urban landscape. However, since for the most part, the urban landscape is defined by dimension stone– sandstone, limestone, marble, and granite– for this, we need to look at the sources of these materials to understand how these materials shape our city.

The urban landscape I call “stone footprints” for the most part is defined by technologies at stone saw mills, which are far from local stone workers. But here I will focus on the small but important part of our past. The stonecutter, a long forgotten trade.

This is my personal understanding of the stonecutter. I have for most of my life lived on the West Coast, so I can speak little of the great body of stone history mostly located on the East Coast. So, my knowledge is somewhat local and does not include the work of marble cutters, again the result of geography. And of course, it excludes the monumental efforts of European stone workers of the 13th through 15th centuries.

A stonecutter by definition is one who cuts a stone by hand to a specific size to fit in a specific location among other cut stone pieces, making the whole, most often for a building.

I donated a book to the stone museum some years ago outlining the work of the stonecutter. It was about 45 pages, 5˝ x 7˝ pocket manual, filled with geometry, math equations of shapes describing solutions to architectural problems.

I think these sorts of working manuals existed for many trades, then. It was very complex reading, so I couldn’t understand much. Imagine cutting a circular stair casing complete with step, facing, outside, and inside walls, with a circular base, the handrail and banisters in granite or marble.

For columns that fit, cutting the flutes in columns, arches, doorframes, windows frames, sloped sill coping, floors and ceiling radial patterns, or grades that wrap around a city block and align perfectly. A lot of three-dimensional math is required.

The first job I had in this industry was laying out large complex shapes full-size on the floor of a pattern room, then making zinc templates of each piece for stonecutters to apply to individual stone while shaping it, in 1959.

I don’t know if early stone cutters had the luxury of such pattern making, but developing complex shapes in three planes with stone was part of their job. I presume to know a little, but my father and my two older brothers could calculate what dad called ramp and twist. My younger brother who was an artist in stone also could, but I could not.

The modern era of the stonecutters in the United States was from 1800 to 1920, when they were replaced by the gang saw (for the most part) although they still exist in large architectural and Memorial fabrication facilities is in the Midwest, East and Southeast, with the help of sawn slabs. I read once that there may be 300 stonecutters left in the United States.

I briefly apprenticed in a fabrication facility cutting dies, slants, hickeys and bases for monumental dealers. They mostly used 6 inch and eight inch sawn or polished slabs of granite.

Stonecutters talk of the subtleties of each type of granite amongst themselves. They all pitch differently. These Memorial cutters are offended by point marks or ill-defined corner lines, a sign of failure in stone cutting.

You won’t survive as a memorial cutter if you can’t drive a clean pitched face on a 10˝ slab of granite, cutting from two sides with the handset and a specialized stonecutter’s hammer. Stonecutters would stun a modern stone worker or government ergonomics inspector. No stonecutter could work with bent elbows. Swinging a 1-1/2 to 3 pound hammer 8 hours a day requires the work to be at hip level.

You won’t survive as a memorial cutter if you can’t drive a clean pitched face on a 10˝ slab of granite, cutting from two sides with the handset and a specialized stonecutter’s hammer. Stonecutters would stun a modern stone worker or government ergonomics inspector. No stonecutter could work with bent elbows. Swinging a 1-1/2 to 3 pound hammer 8 hours a day requires the work to be at hip level.

Apprentice cutters were called lumpers whose job was to shovel up spalls for the stonecutters. I think there were many extra labor jobs back then. I met a stone polisher in Portland in 1968 who told me he knew my uncle Ted, a bricklayer and stonemason when he was a teenager working as a water boy for masons. Back then marble setters (installers) wore white shirts and ties in Portland in the 1920s and ’30s.

Even though I worked in the stone trade for 15 years and had four years of college, I needed to attend a year-long Saturday brick layer school and serve a three-year apprenticeship before I was given a marble masons union card in 1975. Standards for craftsmen then were much more rigid, but today almost anyone can call himself a stone artisan.

My father told me that there were 2,000 stone workers living in the Knowles, California granite quarry in 1920 when he worked there. They were building San Francisco’s city, state and federal buildings, post offices, courthouses, City Hall and the Customs house.

To me, these buildings are the most beautiful parts of San Francisco, all of which were built out of Sierra Nevada granite. We walked around several abandoned quarries looking at granite foundations of stone bunk houses in the lonely foothills of Madera County California. All gone now, flowers, live oak, and abandoned quarry holes full of water. They are on private property ranch land, with no easy access. These old quarries exist all over the country, a remnant of another time.

Back then the stonecutter traveled from job to job, city to city, following the work. They worked with local materials, giving rise to the urban identities we can still recognize. This was well before modern day mass production steel frame, stone skin buildings.

In fact, I often visit the Central Montana town of Lewistown. Croatian immigrant stonecutters, who settled there in the 1800s, built it out of local sandstone. When I first visited, no one seemed to know the source of the stone. After making inquiries, I found my daughter-in-law’s great aunt Mary, who was ready and willing to help me. Two years later she took me to the town’s old quarry. We took some pictures. There is a strong sense of local pride in Lewistown where the old stonework has not been painted over or covered by trendy designs.

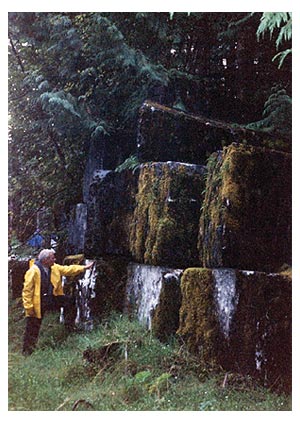

I have spent five working vacations attempting to reopen old marble quarries in Southeastern Alaska (once owned by the Vermont Marble Company). These quarries provided much of the stone used on buildings throughout the West, where 60,000 blocks remain in the rain forest there on Marble Island. A pile of white marble, 40 feet long, 40 feet high and 3 miles long still lies on the ground covered by thick layers of moss.

I have only found four places in the world where traditional stone cutters are still celebrated, by showing their tools in display cases. There may be others. The first is the State Historical Center in Helena, Montana and, second, a state building in Vienna, Austria. Both honor stone craftsmen.

I have only found four places in the world where traditional stone cutters are still celebrated, by showing their tools in display cases. There may be others. The first is the State Historical Center in Helena, Montana and, second, a state building in Vienna, Austria. Both honor stone craftsmen.

The third is the Stearns County Museum in Minnesota, where I grew up. This building is located next to a granite quarry that is now used as a nature park. It has a sunken man-made exhibition quarry in it, showing the tools of the trade. It is a shame that Tenino, Washington does not have an exhibition since its community pool is an old quarry.

The Vermont marble company has a museum that recalls when their company once controlled almost all the marble work in the USA. However, it’s more gratifying when noncommercial individuals provide the history lesson. It seems to suggest a more sincere interest.

As my father and I continued walking around the abandoned quarry, he told me stonecutters of his era were paid a dollar per hour and train fare to and from their home state. Great wages.

By comparison, electricians received 60 cents per hour at the same time. No wonder the stonecutters strutted the streets of San Francisco with their wooden, foldup tape measures in their back pockets on Sundays.

I don’t know the exact delineation of jobs, but stonecutters worked at both the quarry and the actual jobsite at this time. In 1965, I was visiting with a 75-year-old memorial dealer from the bay area. He joked that so much stone dust came from a job shack that the insurance rates were so high, they reached up to the business across the street in to San Francisco. In that era, some lived, some died. My father told me he never expected to see 40 years. His three stonecutter brothers didn’t live beyond 45.

Later, Dad and I came across a piece of granite, five feet wide, five feet long and six inches thick, lying among the wildflowers. All the edges were rough split, top and bottom, broken face.

Interestingly, there was a perimeter of 3 to 4 inches of point marks all around it. I asked my father what this was. I can still see him 50 years later. “You don’t know? That’s a level seat! The stonecutter prepared this stone for the surface drifter to hammer-point the top flat to his marks.”

Years later it dawned on me, this is the fundamental beginning of every building stone ever cut. The stonecutter from 1900 to present had the advantage of compressed air to help them shape the stone, but it still all begins with a level seat, the stonecutters first step.

So, for the sake of experimentation, let’s think of the process stonecutters must have used before Ingersoll’s book, “The Uses of Compressed Air,” was published around 1895. I can only speculate the work of the stonecutter before compressed air.

Joseph Conrad has fifty years experience working in the stone fabrication industry. He is the founder of Conrad Stonecutter in Portland, Oregon (www.conradstonecutter.com) and a 15-year member of Northwest Stone Sculptors Association, www.nwssa.org.