A Community Built of Crab Orchard Stone

By Joel Davis

Photos Supplied CourtesyVicki Vaden and Cumberland Homesteads

IN the dark days of the Great Depression, the U.S. government laid the foundation for a new community in Cumberland County, Tennessee. That community was built on a foundation of Crab Orchard Stone.

IN the dark days of the Great Depression, the U.S. government laid the foundation for a new community in Cumberland County, Tennessee. That community was built on a foundation of Crab Orchard Stone.

Located south of Crossville, the 10,000-acre Cumberland Homesteads Historic Site celebrates the legacy of the Subsistence Homestead Program, which was created through the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933.

The program literally built a working community of 250 homes from nothing, according to Vicki Vaden, a third generation homesteader who has been involved in promoting and preserving the history of the community.“We wouldn’t have a community without it,” she said. “It was literally a community-building project.

This was one of 100 similar projects that were built across the nation. We were one of the first and one of the largest. The government did a lot of experimental things here and evaluated them as they went along.

Things they learned here, they were able to use in the other New Deal communities across the nation.

”The historic homes are now privately owned, but the non-profit Cumberland Homesteads Tower Association preserves the history of the area by operating the Homesteads Tower Museum and the Homesteads House Museum.

Preserving the history of the Cumberland Homesteads has a very personal meaning for Vaden, whose mother still lives in a Homestead house.

“My grandparents on both sides of the family were original homesteaders,” she said. “I’m a third generation. My mom and dad got the museum going.”The NIRA included $25 million in funding for the Subsistence Homestead Communities Program. The vision of the program was to create new, self-sustaining communities for people left unemployed by the Great Depression.

The centerpiece of the community is the eight-story Homesteads Tower, which was constructed with ubiquitous Crab Orchard Stone.

It was built in 1937 to house the government administrative offices of the Cumberland Homesteads.“The tower is a unique structure,” Vaden said. “It was designed by the architect who designed the whole community.

It was the crown jewel, the centerpiece of the community. The government offices were located at the base of the structure in four wings. The tower itself hid a 50,000 gallon water tank.

”The tower is a work of beauty and craftsmanship. “The interior stonework you see as you go up the spiral staircase is just as beautiful as the exterior. Incredible, the skill the masons put into it.

”The human touch of the artisans who built the tower are still evident if you look in the right places, Vaden said.

“In the rotunda, you can actually see their fingerprints in the mortar between the stones in the floor.

”Opened as a museum in 1984, the four large rooms at the base of the tower house a gift shop and historical displays.

The museum’s collection includes documentary photos and other items from the founding of the community in the 1930s and through its continuing development in the 1940s.

The tower, the legacy of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, is located 4 miles south of Crossville, TN at the junction of Highways 127S and 68. In addition to the Tower Museum, the association operates the Homesteads House Museum at 2611 Pigeon Ridge Road in Crossville.

The home has been restored to 1930s condition and is furnished with items provided by original homesteader families.

Architect William Macy Stanton designed the community and structures, which were built over a four-year period from 1934 to 1938.

Architect William Macy Stanton designed the community and structures, which were built over a four-year period from 1934 to 1938.

Stanton had a vision, Vaden said. “Our architect had just come from Norris, TN, where TVA was building their first dam.

He had been asked to design the workers’ houses up there. He was coming off that project, when the government asked him to design our community.”One of Stanton’s goals was to use local materials that could be easily acquired, Vaden said. “He was a Quaker with a back-to-the-land philosophy.

He looked at what materials were here on the ground that could be picked up and used.

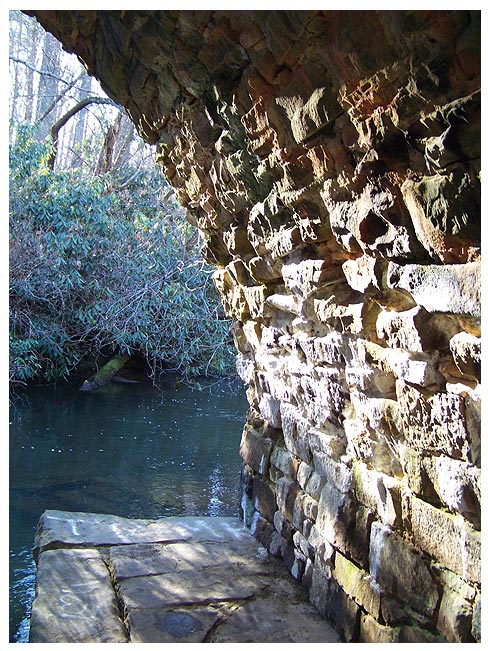

A lot of the stone used was fieldstone, but they also quarried a lot of stone. Everything he designed fit beautifully into the landscape.

”Stanton was known as a collector of unique building materials particularly varieties of wood and stone. He appreciated the beauty of Crab Orchard Stone, Vaden said. “Some of our stone ended up in his fireplace in Pennsylvania.”

The distinctive Crab Orchard Stone is marked by swirls and streaks. It ranges in color from pink to brown to bluish gray. It is a rare durable sandstone named after the eponymous town, Crab Orchard, TN, near which it is quarried.

The stone gained fame after being used in building Scarritt College in Nashville. It was also used in buildings around Crossville such as the Cumberland County Courthouse.

The exteriors of the 250 Cumberland Homesteads houses were constructed of Crab Orchard stone. They were floored with hardwood and paneled with white pine and sometimes oak. Wired for electricity when built, the Cumberland Homesteads would have to wait three years to be hooked up as the Tennessee Valley Authority built its network of dams and power plants.

Stanton took his job very seriously and contributed greatly to the preservation of the community’s history. “A lot of the historic photos we have in the museum archives were taken by Mr. Stanton during the building of the community. He was meticulous to record the date and subject of each photo and his collection is a priceless resource.”

After the Cumberland Homesteads were built, the government began scaling its subsistence community projects back, Vaden said. “They actually got some complaints from some of the senators that this was way too nice for poor folks. But I think it was a chance of a lifetime for an architect like Stanton to be able to design a community from scratch.

They gave him some flexibility. We are still getting the benefit from that.”The Cumberland Homesteads project created a community from whole cloth. It included buildings such as a trading post, cannery, loom house, mattress factory and hosiery mill. A school was built that is still in use today. The first subsistence community built under the program was Arthurdale, W. Va. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt championed its construction. The Cumberland Homesteads came second.

The Division of Subsistence Homesteads purchased 10,000 acres of second-growth timberland from the Missouri Coal and Land Co. just south of Crossville, TN.

The homesteaders came from the Cumberland Plateau and surrounding communities. They included out-of-work coal miners and unemployed people who made their livings through factory or timber work. There were also bankrupt farmers who lost their farms during the Depression. One of the important aspects of the project was the opportunity for men to learn new building trades that would elevate their prospects for finding employment after the community was built.

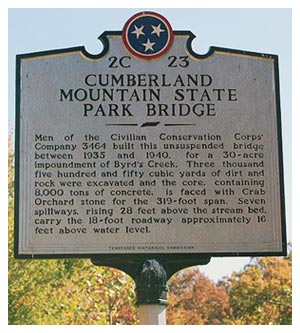

“There were a lot of the homesteaders who learned to be stone masons,” Vaden said. “Many followed that trade the rest of their lives.” She believes the extensive use of Crab Orchard Stone in the buildings and bridges at the Homesteads helped to spur popularity for its use in other structures around the region.

“Those families were chosen to work together,” Vaden said. “One of the things they agreed to do was look out for each other. That happens in all communities to some degree, but here it was actually talked about, and they encouraged neighbors to work together. They had a lot of opportunities to become close and they did.

”The original homesteaders are nearly all gone, but Cumberland Homesteads remains as a 10,000-acre historic district. It’s the largest in Tennessee.

The community itself is not trapped in the past, though, Vaden said. “We’ve managed to grow the community itself through the years,” she said. “We’ve had a lot of newcomers, but we still retain our integrity as a historic community through the collective history of what happened here during the New Deal and the stone architecture that survives. It’s just a really sweet place to live.”