Getting to Know Your White Stones

Karin Kirk

Geologist

|

|

Above: Yule marble, quarried in Colorado, was used in the Jefferson Memorial. |

|

|

Above: The caramel hues in Calacatta Gold’s veining pairs well with wood tones. |

|

|

Above: White Macaubus quartzite. Photo courtesy of Stoneshop. |

White kitchens and bathrooms are perpetually popular. White countertops brighten your workspace, add cheer to a room, and cooperate with any color palette or design style. No wonder white stones are constantly in demand.

Geologically speaking, pure white rocks are rare. While there are many white minerals, such as quartz, feldspar, and calcite, they don’t always assemble themselves into a perfectly white rock. That said, there are plenty of mostly white or nearly white stones that offer possibilities for bringing texture and geologic interest to your white countertop.

Marble

A timeless white marble is what many of us envision when we imagine a serene white kitchen or bath. Beautiful marbles have been in use for centuries, and with good reason. They are gorgeous and they never go out of style.

White marbles are usually swirled with darker colors. These veins are remnants of thin layers of clay within the original limestone, which have been transformed into flowing patterns as the rock was heated and compressed.

This metamorphic process squeezes and stretches the rock, producing the wavy movement that characterizes marble and makes us swoon over it. Meanwhile, the original limestone recrystallizes into marble, making it less porous and more dense.

The colors of the veins offer styling cues that can compliment a kitchen or bathroom design. The caramel hues of Calacatta Gold pair well with warm wood tones. Marbles with cool grey veining, such as Montclair Danby, are a good match for contemporary accents like nickel or stainless fixtures. Some marbles have a green hue, caused by the mineral serpentine.

In rare circumstances, geologic conditions lead to an exceptionally pure limestone with no clay or sand mixed in. If a pure limestone undergoes metamorphism, a pure white marble is produced. One example is the Yule Marble quarried in Marble, Colorado, which is 99.5 percent pure calcite. This stone was used to build the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C. . Thassos marble is another example of a pure white stone that offers a sleek, uncluttered aesthetic.

A marble breccia adds a dramatic flair to a classic look. Breccia is a geologic term for a rock that is composed of angular fragments. These rocks were subjected to folding and shearing stresses that caused the original limestone to fracture. Mineral-rich groundwater glued the fragments back together while also lending some color contrast to the rock. Rest assured that a breccia is not weakened because it was once broken into pieces. The pieces have been bonded back together at great depths in the Earth’s crust and have been perfectly intact for tens of millions of years or more. The stone is just as solid as any other.

Super White is an example of a dolomitic marble breccia. It has subtle colors, but a dynamic texture. Perfect for making a statement without overwhelming your design.

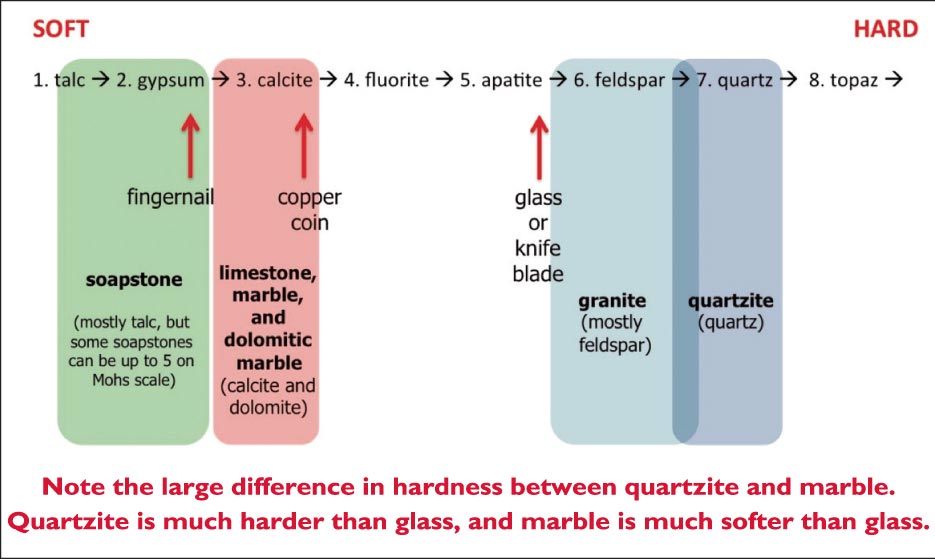

All marble shares similar properties. Most marble resists staining, particularly when sealed. Marble is around 3.5 on Mohs hardness scale, meaning it’s softer than knives and cookware. Perhaps the Achilles’ heel of marble is its tendency to etch when exposed to acids like lemon juice or vinegar. Many people consider marble to be a “living surface” that develops patina and character with use. On the other hand, some of us prefer a stone that won’t show any wear.

Quartzite

Many homeowners face a dilemma as they pine for the classic beauty of marble but worry about its maintenance in a household with small children or a less-than-cooperative spouse. This is precisely why quartzite has become a superstar of natural stone. Quartzite shares the light coloration and the soft pattern of marble, but it contains entirely different minerals. Genuine quartzite is made of quartz, which is 7 on Mohs scale and will not etch from typical acids you’d use in your kitchen. Sounds perfect, right? The downside is the price.

|

|

You don’t need to be a geologist to appreciate the hardness and durability of quartzite. Not only does this make for a tough stone, but it also makes it easy to tell quartzite from the imposters. Quartz is 7 on Mohs hardness scale. That means it’s harder than glass and even harder than a knife blade. These things are easy to test with a sample of stone. |

You can expect to pay more for quartzite for a few reasons. Quartzite is not as abundant as marble and it is considerably more difficult to fabricate. Quartzite’s hardness and density can be a challenge for cutting tools, so be sure your fabricator has experience with real quartzite.

With its best-of-both-worlds abilities, quartzite is in high demand. However, some stones that are labeled as quartzite are actually marble. To further confound the issue, the unfortunate term of “soft quartzite” has emerged to try to account for so-called quartzites that don’t have the properties of real quartzite. This mystery can be easily solved by doing a few diagnostic tests on the stone. (See Quartzite hardness chart, page 45.)

Like marble, quartzite colors can be warm like Taj Mahal, or cool like White Macaubus. For that matter quartzite can tinged with vivid blue, orange, or green.

Granulite

|

|

Above: River White granite, a granulite, formed under extremely high temperatures. |

|

|

Above: Delicatus White granite, a pegmatite, can be recognized by its large crystals. |

Granulite is a geologic name for a class of metamorphic rocks formed under particularly high temperatures. The rock became chemically altered, but it did not completely melt. In the parlance of the decorative stone industry, these stones would simply be called granite. But it’s more fun to use their real name so you can sound extra smart while cruising the aisles of the slab yard. Popular examples of granulite are River White, Colonial White, or Bianco Romano.

Many granulites are white to light grey or light cream color. They are made mostly of feldspar and quartz, with minor amounts of garnets and other darker minerals. Some granulites have a gentle linear or wavy pattern, while others are evenly speckled.

Compared to most granites, these stones can be slightly more porous. They require regular sealing to prevent staining. Granulite has the same hardness as other granites, around 6 on Mohs hardness scale.

Granulites are an excellent choice for a durable, trouble-free stone that won’t break the bank. They have just enough movement and personality to be interesting, but their light, even coloration allows them to play well with other colors or patterns.

Pegmatite

Pegmatites are a special type of granite that have huge crystals. They have a bold texture that is primarily white, cream, or light grey. Pegmatites form in the same manner as regular granite: from liquid magma that slowly cooled underneath the surface of the Earth. But pegmatites have extra-large crystals because water circulated through the magma chamber, accelerating the process of crystal formation.

Patagonia granite is one that will stop you in your tracks in the showroom. The iceberg-sized minerals are geologically fascinating. In some cases, a single mineral crystal can be several feet long. The porcelain-white crystals are feldspar, while the light grey ones are quartz. Rectangular-shaped, black minerals are hornblende. These are the same minerals that are in normal granite, only supersized!

If you want something with a little less drama, consider a pegmatite with crystals that are large, but not huge, such as Mystic Spring, Alaska White, or Delicatus. These stones are predominantly white, but they have some pattern and movement in them too. (See the May Slippery Rock for more about the geology of pegmatites in A Moment in Time: Telling the Stories in Natural Stone.)

Whether you’re drawn to a strongly patterned pegmatite or a demure marble, you’ve got many possibilities for white stones. Next time you find yourself wondering exactly what you’ve got in your stone showroom, take a moment for a closer look at these geologic beauties.

Karin Kirk is a geologist and science educator with over twenty years of experience. She has taught college level geology, online courses and organized field trips. She currently works as a freelance science writer and education consultant. She brings with her a different perspective to the stone industry. Karin most recently presented a program at TISE 2017.