Weeping Water Stone Works

Tom Stander Builds a Firm Foundation Working in Historic Weeping Water Limestone

Shannon Carey

Photos Courtesy Weeping Water Stone Works

|

|

Above: Weeping Water town sign, designed and built by Stander using the local limestone that made Weeping Water famous. |

|

|

Above: Limestone medallion in dry set patio flags. Stander: “The stone in these photos is all limestone from Weeping Water. The gold colored limestone is found close to the surface in ledges and has been harvested since the mid 1800s; the white colored vine table is from the mines which have been quarried since the mid 1950s.” |

|

|

Above: Some of Stander’s tools of the trade against a repaired wall using recovered stone. |

|

|

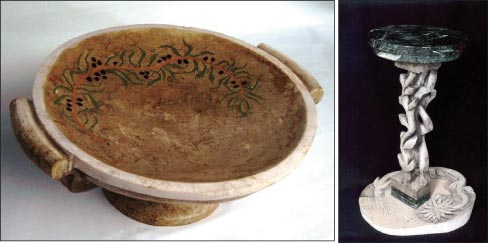

Above: Weeping Water limestone also is carveable. Stander uses it for memorials, headstones, and functional decorative pieces like this bowl and vine table. |

The quarry town of Weeping Water lies close to the Missouri River in southeastern Nebraska, and it’s a town with two well-kept secrets: a special “living rock” limestone and the mason-turned-sculptor who loves it.

Tom Stander runs the one-man show that is Weeping Water Stone Works, and he’s taken up the cause of this often-discarded stone that he calls Weeping Water Wall Stone. Gold in color, the stone comes in ledges that local quarries strip away to get at deeper, whiter layers of stone. Stander said the gold stone was used locally as a building stone, but it stopped being used in the 1920s or 1930s. It forms much of the historic infrastructure of Weeping Water itself, including the Weeping Water Academy, the Weeping Water Congregational Church, and even parts of the Fort Crook House in Omaha.

“It would be nice if I could get it to be used more in veneers and decorative work, mosaic, flagstone walks,” said Stander. “It should be utilized. It’s very durable, it’s hard, and it’s got a good burnish. It’s been exposed to the elements for 147 years, and it has very little weathering or deterioration.”

One interesting facet of the Weeping Water Stone is its tendency to “bleed.” Over the natural course of the stone, iron oxide will surface and bring a rusty color with it. While some people think of that as a detriment, it’s something that Stander treasures.

“I think it’s just a natural process like a wrinkle on a person’s face,” he said.

Stander started off as a mason and has done both commercial and industrial masonry. Back in the late 90s, he donated a carved stone to the Limestone Days auction in Weeping Water. It said “Weeping Water, Nebraska, Home Of The Rock.” He mentioned to someone on the Weeping Water School Foundation that he was interested in attending a stone carving school in Vermont.

Soon, the foundation awarded Stander a full scholarship to attend Vermont’s Carving Studio.

“I was overwhelmed by people’s ability to work marble,” Stander said. “I came back with as many techniques as I could remember and started doing little projects.”

Weeping Water City Council hired him to design and build a welcome sign for the city, which he did out of Weeping Water stone.

“I got the job, and I didn’t really have much,” he said. “But my mother loaned me $1,400 for a portable air compressor. I was so grateful that someone stood behind me with actual money. Everything came out really well, and I paid her back.

“My business, it grows by the kindness of others.”

Stander gained more acclaim when one of the Romanesque buttresses of the old Weeping Water Academy started to crumble. The building, built in the 1860s, had been a school, a church and finally a library.

“I tore the bad one down,” said Stander. “It was winter. I was trudging through snow. I would put up blankets and heat the ground.”

Then one day, he got a surprise.

“I hit something that was metal,” he said. “I thought, ‘Oh, gosh! I’ve hit the water line.’ But then I remembered that they didn’t have a water line when this was built.”

There, in a cavity near the bottom of the buttress, was a tin and pewter time capsule, forgotten in the march of years. And by happy coincidence, it was the 150th anniversary of the building. But unfortunately, all the contents of the time capsule had crumbled to dust, save for one corner of a Bible.

The city placed a new time capsule under Stander’s new buttress, and Stander included a hand-carved cross made from the stone of the old buttress.

Stander is a man-of-all-work in the stone industry. He does restoration and repair, decorative work, even sculpture.

In his masonry repair work, he tries to rebuild out of the same material and painstakingly match the mortar.

“I do whatever I can to make a living,” he said. “I love to work with stone. I’ve worked out of the back of a Buick. I do all my carving in my backyard.”

|

|

Disassembly before restoration of the Weeping Water school building, built in the 19th Century. The red spots or iron oxide stains are part of the characteristics of old Weeping Water stone installations. |

His tools include a steel cut-off saw, a flaming tool, grinders, chisels, hand-carving tools, and polishing pads he buys from Braxton-Bragg. He compared Braxton-Bragg to an old-timey hardware store that’s just as helpful with customers coming in for “just one nail.”

“When you complete a project, it’s very gratifying,” he said. “You know, it’s just kind of hand to mouth, and I would like to grow and share the fruit of that growth with others. I don’t want to grow just to grow.

“The oak trees around here, they grow in really rocky soil, and the roots twist around in the soil around the rocks, and that is like the progress of Weeping Water Stone Works.”

Which brings us back to a Bible verse from Isaiah 58:12. Stander said that verse is a touchstone for him.

“Repairer of broken walls,’” he said. “I read that a long time ago, and I really liked it. Before that, it talks about sharing your gifts and helping other people. That’s where I’m at.”

For more information on Weeping Water Stone Works visit online at www.weepingwaterstoneworks.com, or call 402-227-5186.