A Blueprint for the Future

One City Reverses Course in Pursuit of Sustainable Development

Iyna Bort Caruso

Reprinted from usenaturalstone.com

|

|

Above: REI Corporate office, featuring Chestnut Shell Kansas limestone. Photo courtesy of U.S. Stone Industries |

|

|

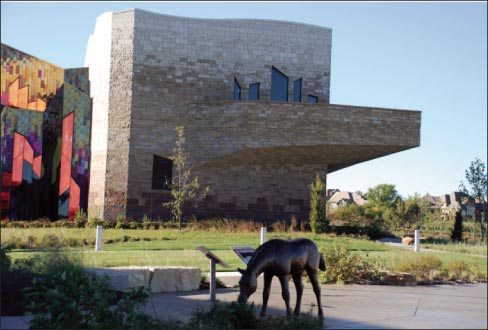

Above: The Prairie Fire Museum features Chestnut Shell, Flint Hills Mottled, Prairie Shell, and Cottonwood Kansas limestone. Photo courtesy of U.S. Stone Industries |

|

|

Above: Charles Schwab corporate office – Cottonwood Kansas limestone. Photo courtesy of U.S. Stone Industries |

About 10 years ago, officials with the city of Leawood, Kansas, began noticing problems with some of the city’s commercial buildings. Facades were chipping, others fading. And the problems were occurring in buildings only a couple of years old.

Leawood is a post-World War II community. It is also a success story. This Kansas City suburb, just about 10 miles southwest of downtown, is home to the wealthiest zip code in the state. Its population — just shy of 32,000 — has more than doubled since 1980, and its commercial development is a fast-growing sector of a fast-growing real estate market.

Which is why construction woes in newer buildings raised red flags.

Mark Klein, a Leawood planning official, says brick dominated commercial construction up until around 2003. That was about the time when architects started to propose using manufactured stone for a number of new projects, which were approved for commercial use by the city. Leawood’s planning commission reviews detailed building plans for every proposed development and like a lot of municipalities sign-off is based, in part, on whether a given project reflects the community’s heritage and is true to its architectural integrity. “Unfortunately we started running into problems,” Klein recalls. Some quality control issues were related to poor installation. The man-made stone was actually falling off the buildings. Klein noticed fading on some exteriors and chipped pieces on others. “They looked like stone on the outside, but when it broke you could see the concrete. It ruined the illusion of a stone facade.”

Around 2005-2006, the commission started to question whether construction using manufactured stone siding should continue to be greenlighted. Klein and his colleagues toured stone yards, spoke to experts and educated themselves on the properties of both simulated and natural stone. “For one thing, natural stone needs to be installed by a stone mason so there’s already a higher level of skill involved,” Klein says. “And if it breaks, it still looks the same. It doesn’t fade, it’s more durable and there’s less chance of it ripping off the building than its man-made counterpart.”

Manufactured or man-made stone is a concrete mix poured into molds and then colored so it resembles the tones and textures of quarried rock. By contrast, natural materials like limestone, sandstone, and granite have proven durability. For jobs such as retaining walls, pavers, bridges, and buildings, they age gracefully and weather well.

Only diamonds, rubies, and sapphires, for instance, are harder stones than granite. Most limestone has a uniform texture that ages gracefully over time to a nice patina.

“When we talk about natural stone, there aren’t many products more sustainable, especially compared to man-made,” says Steele Crissman, Vice President Sales and Marketing at U.S. Stone Industries in Kansas City. The company is a quarrier, fabricator, and distributor of Kansas limestone with roots that go back to the 1930s.

The green aspect starts with how stone is procured. “We’re taking a natural resource and not doing anything to it with chemicals. We’re using some diesel fuel, some water, and some electricity to cut it out of the ground. That’s it,” Crissman says. “From extraction to production to shipment, we’re pretty earth-friendly.” The stone is a high yield resource with not a lot of waste. What doesn’t end up on a job site doesn’t end up in landfills either. It’s crushed and used for gravel fill or concrete aggregate. Even stone from torn-down buildings can be repurposed.

Stone companies work with masons, builders, homeowners and/or architects in the design and budgeting process. An architect who had submitted plans to Leawood for a new senior development originally included manufactured stone in his specs. Although the city doesn’t have ordinance that specifically prohibits manufactured stone, natural stone is enthusiastically encouraged. The architect went back to the drawing board and replaced precast stone with natural, working with U.S. Stone Industries on sourcing the materials.

Economics, of course, is a major driver in such decisions. However, while some builders propose manufactured stone because they’re concerned with the bottom line, Leawood city officials are more concerned about the durability of the product, what it will look like in 10, 20 or 50 years’ time and how a remodel or an addition down the road could affect a building’s overall aesthetics. With natural stone, they’re assured the material is going to be around and it’s going to look the same.

It helps cities like Leawood that prices associated with natural stone are going down. Marketplace efficiencies have made initial cost less of a factor than in the past. Advances in quarrying, processing technology and machine automation allow fabricators to cut faster and more consistently. The results are falling square-footage costs that are enabling natural stone to be more competitive with man-made. “Our job is to make that case to people and use the experiences of Leawood, Mission Hills, and other cities to show them the value,” says Vanessa Cobb, a project manager with U.S. Stone Industries.

In the region, Leawood was one of the first cities to back off manufactured stone, Klein says. Now other cities are starting to do it as well.

The nearby Kansas City suburb of Mission Hills has issued some of the most comprehensive design guidelines in the country. Natural stone is the material of choice for this country club community of single-family homes that Forbes ranked third in its list of most affluent neighborhoods in the U.S. just a few short years ago. Synthetic materials and those that attempt to simulate natural stone are discouraged. According to Mission Hills guidelines, natural stone plays an important role in a “home’s ability to ‘fit into’ its neighborhood context” and reflects an intention to building a community of permanence and quality. “It’s all about property values,” says Crissman.

“It ensures somebody doesn’t come in and put up some crazy modern structure that doesn’t go along with the more traditional brick and stone homes or put in something too cheap.”

Says Leawood planning official Klein, “Going and encouraging builders to use natural stone is definitely the direction the city is going on and it’s worked out well.”