Varmint County: Flotilla Arrives in Crescent City, But Granny Haig Conquers Music City

Boomer Winfrey

Varmint County Correspondent

|

|

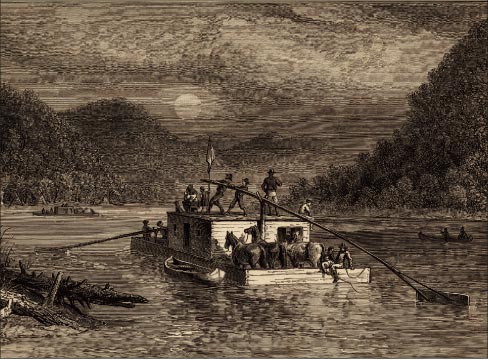

The plan was to recreate those early trips as closely as possible, using long poles to steer the boats in shallow water, long “sweep” rudders to steer and power them in flowing water and square-rigged sails for moving through deep, windy lakes. |

Just about three years ago, an unlikely cast of characters boarded three wooden flatboats to begin a 2,000 mile trip from the base of Mud Lake Dam to New Orleans, re-enacting trips made two centuries ago by Varmint County’s early settlers to trade with the Haig Clan in Louisiana.

The plan was to recreate those early trips as closely as possible, using long poles to steer the boats in shallow water, long “sweep” rudders to steer and power them in flowing water and square-rigged sails for moving through deep, windy lakes.

With a strong current released from Mud Lake Dam, the boats traveled uneventfully for the first dozen miles or so, crews using the poles to fend off the banks and streamside brush while helmsmen used the sweep to steer around bends.

Boat number two did have that one incident, when Clyde Filstrup Junior tried his hand at handling one of the poles. Clyde dug his pole into the sandy bottom of the Muddy Branch of the Little South Fork and pushed, following along the deck to the stern of the boat. Then he forgot to pull the pole up in time, with predictable results.

“Hey, Clyde, you look kind’a funny hanging there on that pole in the middle of the river. You want we should take your picture?” Archie Aslinger asked.

“Don’t just stand there gawking, Archie, get me back off this thing and on the boat.”

“Sorry, Clyde, we’re down current and we can only go one way. You’ll have to swim for it.”

About that time, Ike Pinetar steered boat number three alongside Clyde Junior, and Cooter McBean pulled him on board. “Hey, Archie, we found one of your strays hanging out here in the river. Want us to bring him to you?” Ike yelled across the water.

The Varmint County Bicentennial Flotilla passed the rest of the day uneventfully, bouncing through the swift, shallow waters of the Muddy Branch into the slightly deeper Little South Fork. The crews had a brief moment of tension at the “Narrows,” a series of short drops over rock ledges, that with one false move, could have easily wrecked the wooden craft.

Penny Haig and a dozen of her strapping cousins lined up on the bank with a tow rope and lowered the boats, one by one, through the deepest channel between the rocks, and the whole fleet passed without incident.

Late that evening, the flotilla emerged at their first day’s goal, the junction of the Little South Fork and the mighty Cumberland River, flowing strong and swift out of the hills of Eastern Kentucky.

Their good fortune didn’t last for long. By the time the sun dropped behind the hills, the current had completely ceased and the boats bobbed helplessly in the backwaters of Lake Cumberland, going nowhere fast.

“There’s no wind for the sails and the water’s too deep for poling. We’re stuck here ‘til the wind picks up,” Archie sighed.

“Nope. Tie that tow rope to my stern and get another rope to boat number one. It’s time for Ike’s little contingency plan to be put to work,” Ike Pinetar instructed as he hauled the outboard and gas can on deck.

“Don’t you think that’s cheating a bit, Ike?” We’re supposed to be re-enacting the trip like it was 1814. They didn’t have outboard motors back then.” Toony Pyles protested.

“Yeah, well they didn’t have Wolf Creek Dam backing up 80 miles of the Cumberland River into a lake back then, either. Gotta adapt with the times, I suppose,” Ike replied. “Y’all jest tie these boats together and go into the cabin and get some rest. Let ol’ Ike handle things.”

And handle them he did. By ten o’clock the next morning, all three boats were pulling into the landing ramp above Wolf Creek Dam.

“We’re two days ahead of schedule,” Penny Haig observed.

“We’re gonna need those two days,” her sister Chloe added. “How are we supposed to get these boats around that dam into the river below?”

“Ike, I thought you said we could pass through the locks on all these Army Corps dams?” Clyde Junior whined. “Where’s the lock?”

“Well, Clyde, nobody’s perfect I guess. There don’t seem to be a lock on this here dam.”

“What’cha doing with that cell phone, Penny?” Ike Pinetar asked Penny Haig.

“Calling Grandpa Elijah. We’re gonna need some divine intervention or a crew of strong backs and weak minds if we’re going to get around this dam.”

Since divine intervention seemed in short supply that day, Elijah Haig soon arrived from Varmint County, followed by a dozen pickups loaded with Haigs and Hockmeyers, and two logging trucks loaded with pine poles.

“I think we got enough manpower to roll these boats on poles up this ramp and down to the river,” Elijah said. “You got any more surprises for us on downriver?

“Nah. I talked to the guy in charge of the fish hatchery and he told me all the other dams on the Cumberland River have locks to handle barge traffic. They didn’t build a lock on this dam ’cause there ain’t no towns between here and where the river drops over Cumberland Falls.”

By early the next morning, all three boats had been hauled across the dam and the highway and into the river again. Granny Haig had several people helping her cook up a huge pot of beans and bacon while she turned out several dozen pans of cornpone from her wood-fired Dutch Oven.

“You boys been working hard. I need to feed you all good before you head back to Haig Hollow,” Granny announced as she spooned out platefuls of beans and sliced off chunks of onion.

“I’m sure glad we’re riding in the back of the pickup bed,” Corney Haig told Caleb Hockmeyer as he watched his companions wolf down the beans and corn pone. “I’d hate to be trapped inside.”

Thanks to Ike’s motorized crossing from the night before, the entire portage of the flotilla was accomplished without falling behind schedule, which was a great relief to Granny.

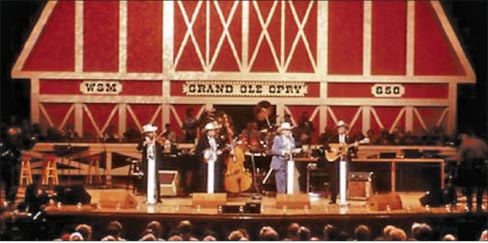

“I promised Granny that we would get to Nashville Saturday afternoon so she can go to the Grand Ole Opry. She’s listened to the broadcast on the radio for more than 50 years but has never been to the Opry,” Archie told Elijah. “Thanks to your boys we’re back on schedule to make it.”

|

|

Saturday night, Archie, Penny, Chloe and half a dozen others accompanied Granny to the Opry, where George Straight, Mel Tillis and several other headliners were scheduled to perform. But it was the house bluegrass band that brought the house down that night, or rather Granny Haig. |

Saturday night, Archie, Penny, Chloe and half a dozen others accompanied Granny to the Opry, where George Straight, Mel Tillis and several other headliners were scheduled to perform.

“I don’t understand it. Where’s Minnie Pearl?” Granny asked.

“Uh, Granny, Minnie Pearl’s been deceased for a right smart time now.”

“Oh, that’s right. I forgot. I guess Grandpappy Campbell and Roy Acuff are gone, too.”

“Afraid so. You’ll have to settle for some of these younger folks, like Hank Williams Junior or Charlie Daniels,” Penny chuckled, thinking of country music performers who are already getting rather long in the tooth.

But it was the house bluegrass band that brought the house down that night, or rather Granny Haig. The band ripped into a lively fiddle and banjo tune when suddenly Granny got up in the aisle and started clogging.

Pretty soon the whole audience was clapping along and then George Straight leaped off the stage, began clogging alongside Granny and led her up onstage. Granny clogged circles around everybody until the tune ended.

“That’s some good moves you got there, little lady. How long you been clogging?” George asked.

“Don’t rightly remember exactly. Since I was about six or seven, I reckon.”

“If you don’t mind me asking, how old are you now?”

“I don’t rightly know that either. I remember Cleveland.”

“You were born in Cleveland?”

“No, young man. I was born in Haig Hollow. I was born when Cleveland was President, or maybe before he was President, ’cause I remember him. He got married to that sweet young girl while in the White House.”

“Quick, somebody tell me when Grover Cleveland was President!” George Straight called out to the crowd. “1892 – No, 1896!” somebody yelled back.

“Well, Granny from Haig Hollow. I reckon that makes you about the oldest person to ever perform at the Grand Ole Opry! Will you favor us with another dance?”

By the time the night was over, Granny Haig had become an instant celebrity in Music City. She was given a lifetime pass to the Opry, invited to go on tour with Taylor Swift and invited to visit the State Capitol to be honored as the state’s oldest citizen.

“I’d like to do all them things, but I can’t. I gotta feed three boatloads of hungry folks on our way to New Orleans. They ain’t got nobody else along that can cook up vittles for three dozen hungry mouths,” Granny declared.

The Varmint County Bicentennial Flotilla began its journey with little fanfare, quietly slipping out of remote Varmint County and noticed only by a few amused fishermen along the banks and the occasional Army Corps lockkeeper who had to trouble himself to let the three boats pass through.

After the Grand Ole Opry that all changed. Crowds lined the shore at every town the little fleet passed through – Clarksville, Paducah, Cairo, Illinois, until finally the boats drifted out of the mouth of the Ohio River and onto the mighty Mississippi.

At Memphis, the city fathers had prepared a big welcome, with Granny Haig as the Matron of Honor. She was given a tour of Beale Street and Graceland, where she asked, “Who lived here? You could fit everybody in Haig Hollow in this one house.”

“This was Elvis Presley’s mansion,” the Mayor explained.

“Elvis who?” Granny asked.

Penny and Chloe snickered while the head of the Graceland Foundation tried to hide her shocked expression.

The flotilla continued down the Mississippi, stopping briefly at Vicksburg, where Granny and the other Haigs laid a wreath at the tomb of Colonel Lejuane Haig, who perished in the siege of Vicksburg in 1863, killed when a still he had constructed to distill whiskey from turpentine exploded.

Less than five weeks after leaving Varmint County, the flotilla pulled into the levee adjacent to Jackson Square in the heart of New Orleans’ French Quarter, where a couple of hundred Louisiana Haigs had gathered to welcome their hillbilly cousins and of course Granny, who is universally recognized as the Matriarch of both clans.

Nearly everyone who started out at the base of Mud Lake Dam completed the trip, including one that nobody expected to see again, as Arlie Hockmeyer’s brush with the law had finally caught up with him. Along with the welcoming committee in Memphis waiting to wine and dine Granny and her companions, two detectives also met the boats, armed with a warrant for Arlie’s arrest for assaulting a state trooper with a tow truck.

“If you’uns will excuse me, I think I’ll take a little swim over to Arkansas,” Arlie told Cooter McBean and Ike Pinetar, before diving into the river. So it was a pleasant surprise when Arlie showed up at the reception in New Orleans, having hidden out with the Haigs in the Atchafalaya Swamp for the past three weeks.

Absent from the New Orleans reception was Clyde Junior. While Granny was making history at the Grand Ole Opry, Clyde and one or two others had decided to visit Nashville’s infamous Printer’s Alley, home to numerous bars and strip clubs. Clyde imbibed one too many shots of Jack Daniels and was promptly mugged in an alley off Printer’s Alley.

The few lumps and bruises he received would not have deterred him from continuing on the river trip, but his wife Matilda got wind of the incident and drove down to Nashville to retrieve her wayward husband.

“End of the line for you, Clyde. If I can’t trust you to keep out of trouble in Nashville, I can’t even imagine what you’ll do in New Orleans!”

The re-enactment of the Battle of New Orleans went off without incident, except that in all the noise and confusion of the mock battle, Cooter McBean suffered a Vietnam flashback and nearly decapitated two Haigs and the Superintendent of the Jean Lafitte National Historic Park, saved only by the timely intervention of his friend Stanley the Torch.

Finally the weary gang of unshaven and ragged travelers returned to Varmint County just in time for the annual Fourth of July festivities, this year accompanied by roughly half of the performers from the Grand Ole Opry.

“After meeting Granny Haig and hearing her talk about Varmint County, Haig Hollow and the annual July 4th Haig-Hockmeyer fight, I had to see it for myself. Might be we oughta broadcast the Grand Ole Opry from here sometime,” George Straight proclaimed.