Whatever Happened to Joliet Limestone? A Brief History

Peter M. Marcucci

Photos courtesy the Joliet Area Historical Museum and the Dr. Robert E. Sterling Collection

|

|

Above: The stately 19th century Hiram B. Scutt mansion is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and a prime example of the use of Joliet limestone for the foundation, lintels, columns and other structural embellishments. |

|

|

Above and below: Archive photos show the first quarry used in the construction of the Illinois State Penitentiary. The prison was built on top of the quarry using inmates for laborers. The Quarry was run by Lorenzo B. Sanger and Samuel K. Casey. Prison architects were from Chicago, W.W. Boyington and Otis L. Wheelock, who also designed the landmark Chicago Water Tower and the State Capitol. A quarry across the street (at right) was also opened, enabling them to quarry enough stone to finish the immense prison construction project. |

|

|

|

Above and below: Completed in 1869, the 154 ft. tall Water Tower in downtown Chicago is built of Joliet buff and white Limestone. It is the only public building to survive the fire of 1871, although some stone had to be replaced Behind the Neo-Gothic facade a 138-foot-tall standpipe (now removed) helped control the city’s water pressure, when the city’s supply was piped in from Lake Michigan. Now, the tower regulates the city’s flow of tourists. Since the 1970s it has served as a tourist information office and also houses exhibits. |

|

|

|

Above: 19th century engraving shows an aerial view of the Illinois State Penitentiary grounds, including part of ongoing stone processing operations (center of the image). The prison building was used to film the movie Prison Break and also was used in the first Blues Brothers movie, where Elwood Blues picks up Jake, outside a tall, foreboding prison wall. There are a lot of visitors to the Joliet museum, and a top request is ‘we want to see the prison.’ |

|

|

Above: Entrance gate to the Rosehill Cemetery, Chicago, designed by W.W. Boyington. The Gothic Revival crenelated walls and towers were built with Joliet limestone about 5 years before the Chicago Water Tower, c.1864. Rosehill is the largest cemetery in Chicago, with memorials to the Union and Confederate soldiers buried there. It contains the largest number of Union soldiers buried in any private cemetery in the U.S. |

|

|

Above: This unidentified Joliet quarry is using one of the high-tech cranes of the day, loading slabs onto a flatcar. Most likely the stone was destined to be fabricated into facades and foundations. |

|

|

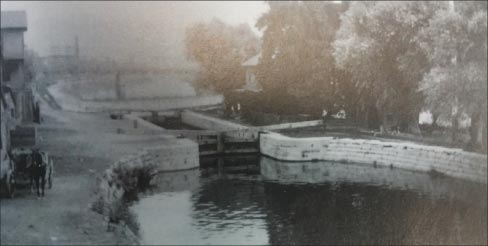

Above: An Illinois & Michigan Canal lock and the lock tender’s house, in Joliet. The lock was removed in March, 1899. “And then there’s the beauty of the old canal locks. It’s pretty amazing to see how they worked. Unfortunately this old lock in Joliet was removed when the canal was improved,” explained Barbara Newberg. |

|

|

Above: A day’s worth of blocks and slabs ready for transport. Judging by their more formal clothing, these men are likely quarry owners or supervisors rather than quarry workers. “Initially, the quarries were shipping their stone by canal, but when the railroads came in, around the 1850s, the stone was also being shipped by rail,” explained Barbara Newberg. Note the hoist chains on this mini flat car of trimmed stone. |

|

|

Above: Restoration in progress of the Joliet limestone flooring installed in the White House. This archive photo shows a stone mason removing the flooring slabs in the North-East corner of the White House main entrance lobby. |

|

|

Above: Quarry men with the tools of their trade – chisels and pry bars – in one of the many Joliet quarries during the heyday. “Initially, the quarries were shipping their stone by canal, but when the railroads came in, around the 1850s, the stone was also being shipped by rail,” explained Barbara Newberg. |

In 1673 Louis Jolliet, a French Canadian explorer, and Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit priest and missionary, first paddled the Des Plaines River.

Noting the rich forests, fertile lands and limestone outcroppings along the riverbank, Jolliet envisioned farms and cities and thought he’d found the perfect stone to build them.

He also envisioned a canal that would add robust growth and sustainability through transportation to and from this city of the plains.

Canals, you see, were the highways of the future, and when combined with the local limestone, the railroad, and cheap labor, would transform rural Joliet into a 19th century growth machine.

The Birth of a City and the Growth of a Young Nation

America, in those days, was still a territory — an explorer’s smorgasbord of resources waiting to be sought out and developed. Scores of decades later, those river outcroppings would be replaced with quarries–over fifty during their heyday, spanning the area from Lockport to Rockdale, Illinois. But it was over 150 years before Louis Jolliet’s vision would reach fruition, according to Joliet, Illinois City Planner and Historian, Barbara Newberg.

“The first settlers began arriving here in 1832. I think it got too cold and they went back to Indiana! Returning a year later, the settlement of Joliet saw development. This was occurring at the same time the local Indian population was being pushed out west. The Indians resisted, settlers were massacred and everyone tried to go into the fort for their safety. This area has remained undeveloped land occupied by Indians until the 1830s.” (See page 17 Sidebar on Fort Nonsense).

Joliet (originally named Mount Juliet) is located 40 miles southwest of Chicago. It was an agricultural community in the early days. Farmers transported their grain to market along dirt roads, but maybe, if a suitable waterway was built, farmers could ship to new markets elsewhere.

Dust, Sweat and Sore Muscles for a Dollar a Day

Fortunately for Joliet and its surrounding area (and partly due to the success of New York’s Erie Canal in 1817), the US Congress had decided to fund a canal for Illinois. In addition, the Illinois border was extended north in 1818 to include Chicago, thereby creating the possibility of a canal entirely within the state of Illinois. Congress then acted in 1822 to authorize funding for the canal. Construction began in 1836.

“It was mostly Irish immigrants who came in to work on the canal,” Barbara describes. “They were being paid a dollar a day.

She continued, “The way I understand production back then, it was based on hard labor using hammers, chisels, wedges and pry bars. Horses would then pull the stone. Early on, there was a man that invented a rock drill, so they would drill into the rock and fracture it. But when the blasting technology became available, they started to do that.”

The earliest quarries supplied major contracts with high quality limestone, but eventually the smaller quarries, which yielded a lesser quality stone, quarried products for foundations, curbs and sidewalks. Referred to as Niagara limestone from the Silurian period, the dolomite strata beds were deposited over a period of 500 million years. There was a yellowish, a light tan and various shades of gray limestone, and it was quarried in blocks and thick slabs. There were also different methods of finishing done by hand, which was also very difficult work according, to Barbara.

“The real difficulties back then were social issues, such as housing, the system of payments and maintaining law and order. In my view, what is incredible here, is that it was like the wild west in those days. Whereas back east you already had developed cities — the early base of Joliet consisted of very rudimentary housing. People had gas lighting and wells, but no toilets, bathtubs or electricity.”

The Canal, and the Railroad that Changed Everything

The year 1848 ushered in many changes for our young nation. The Mexican-American war had just ended, but the Civil War was on the horizon.

Barbara continued, “In the late 1800s, our canal waterway was merged with the Des Plaines River, and a project to deepen the waterways to accommodate barge traffic was begun. Then, eventually, the huge change was that the Chicago River’s flow was redirected outward.”

By 1848, the Illinois & Michigan Canal was complete. The 97 mile long, 60 feet wide, 6 feet deep waterway now connected Joliet to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River, which led to the Gulf of Mexico. By employing 17 locks made with local limestone and 4 aqueducts, the canal allowed barges drawn by mules to deliver products to a growing heartland.

“Initially, the quarries began shipping their stone by canal, but when the railroads came in, around the 1850s, stone was also being shipped by rail. The early shipments were local, but the most notable local use was at the (old) Illinois State Penitentiary in Joliet (now the Joliet Correctional Center), where they quarried the limestone right on site. Construction began in 1858, and they used prison inmates for labor. There were 2 quarries. One was 700 by 700 feet and directly under the prison. As soon as the initial prison was built, prisoners were immediately brought from Alton prison for incarceration. Quarrying was then expanded to a slightly larger quarry across the street.

“The contracts to build the prison were highly political. They brought the board of overseers of the prison to Joliet, and some people were already lined up wanting to quarry the stone.”

“The Rock Island Armory was a huge government contract, and they had to prove that the stone had a certain density in order to get that contract. As the limestone became more popular, sometime between the 1860s and 1870s, it was being shipped to other parts of the country. That’s why the White House has floors of Joliet limestone.”

Notable structures using Joliet limestone include both the old and new Illinois State Capitol buildings located in Springfield; the Chicago Water Tower and pumping station that look like small castles; the Holy Name Cathedral, a well known Catholic Church located in Chicago, and the entrance gate to the Rosehill Cemetery, also located in Chicago. Joliet limestone was also shipped to many other large-scale projects around the country (refer to the links at the end of this article for additional information on other extant Joliet limestone buildings).

The Years of Diversification

If you took a broad perspective on the growth in those days, the prison was done, the canal was built, and now you had this huge labor mechanism. So the city of Joliet decided to get busy offering incentives to move additional industry to the area.

“That was very progressive on the part of the city, and the way they lured the steel industry to come to Joliet in the 1860s,” explained Barbara. “They sold the proposal by saying there were nearby coal beds in Grundy County — a ready supply of fuel to power the steel mill.”

U.S. Steel helped to propel Joliet into a major industrial center in the 1880s. Moreover, Joliet was the wallpaper capitol of the world said Barbara, adding “We had all kinds of industry on our eastside, including factories that produced stoves. If you fast forward to after the great depression, we were still producing steel. There were still fumes from the smokestacks of the steel mill in 1972, but soon after, that the steel industry rapidly declined.”

A Flourishing Industry Deteriorates, an Important Chapter Closes

If Joliet limestone was so popular, why did its use fall by the wayside?

Firstly, as the 1800s came to a close, it was clear that the structures made of Joliet limestone were weathering prematurely, and the stone was judged unfit for further structural use.

Facades were not holding up as well as expected, and the more durable Bedford limestone quarried from neighboring Indiana had become the stone of choice.

It was, however, good for crushed stone to build highways and continues to be. There is a quarry just outside of town, called the Vulcan Quarry, that to this day extracts limestone for gravel.

Secondly, tastes had also changed. The extensive use of cheaper brick and mortar or wood further contributed to the demise of building with local Joliet limestone.

The Joliet Correctional Center has been closed since 2012. It is, however, one of the number one tourist stops in the area. The I & M Canal Trail and adjacent land is mostly used for canoeing, hiking and biking — offering museums and historical buildings to sample along the way.

As for the limestone structures of the day, many do remain — some are pristine, and some, altered. They continue to stand as a testament to the drive, the innovation and the vision of the resourceful builders who didn’t look back.

Regrettably, only a handful of the old quarries remain that bear silent witness to what once was the stone that helped build the heartland of America.

Readers wanting additional information on Joliet City, the I & M Canal or Joliet limestone should Google-search the following keywords or links:

- Lewis University – I & M Canal Archives

- Also: www.americancanals.org/

- Legacy Cast in Stone-Chicago Tribune

- Joliet Lemont Limestone Landmarks Illinois (PDF book)

- Joliet Illinois canal history (Wikipedia entry)

Barbara Newberg is a native of the west suburbs of Chicago (Glen Ellyn) and was an invaluable resource in researching this story.

Thank you, Barbara —