Museum Gets Credentials Booted After Selling Ancient Statue

The North Hampton Museum & Art Gallery in England, which is known primarily for their vast shoe collection, sold its shoeless Sekhemka sculpture.

The North Hampton Museum & Art Gallery in England, which is known primarily for their vast shoe collection, sold its shoeless Sekhemka sculpture.

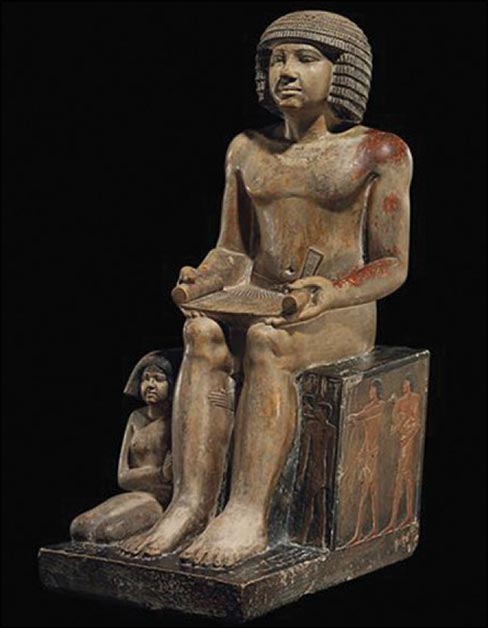

Sekhemka is a 4,500 year old, painted limestone sculpture depicting an Egyptian scribe with his wife sitting by his side. The sculpture dates from the 4th dynasty– roughly the century when the Great Sphinx and Khafra (second-largest) pyramid of Giza were built.

Word of this sale caused quite a ruckus.

Digital storm clouds gathered as an internet protest was created on Facebook in October 2012 by an organization calling itself the “Save Sekhemka Action Group.” The SSAG adamantly opposed the proposed sale of the artifact that was going to be conducted through the renowned auction house Christies of London.

Through that social network platform, protesters raised awareness by passing historical information about Sekhemka and updates on the potential sale. SSAG, continued rabble rousing throughout the next two years until the day of reckoning came.

Doomsday for the SSAG came on July 10, 2014 when the Sekhemka sculpture was auctioned through Christie’s to a private collector for $27 million. The initial estimate was an $8-10 million sale. Half of the proceeds are going back into museum coffers.

In England, small museums like The North Hampton Museum & Art Gallery are funded by local governments who are also in charge of providing housing and basic social services. It is noteworthy then that a visit to The North Hampton Museum & Art Gallery is free to all visitors. The phenomena of free museum entry is quite common across Great Britain, in a time when these museums are commonly under-funded due to the pressing priorities of local governments.

Keep all those pertinent facts in mind.

Museums are the banks of cultural treasure, with written and unwritten agreements that make the action of selling the sculpture to a private collector, egregious to some and a fiscally wise choice to others.

There were those who pointed out that the Sekhemka sculpture had not been publicly displayed four years prior to the sale as it was less costly to store than to show.

Right around this time, a well-known politician started voicing his concerns about the sale. The Egyptian Ambassador to Britain, Ashraf Elkholy, commented on July 11 that Sekhemka belongs to Egypt and if the Northampton borough council does not want it then it must be given back.” (CCP)

A childish argument to say the least.

Sekhemka was brought to England in 1850. According to The Committee for Cultural Policy, “The government of Egypt has condemned the sale of the statue of Sekhemka, a royal scribe, which left Egypt legally 164 years ago and has been in the collection of the Northampton Museum since 1880.”

It appears that no transfer of an Egyptian work of art is legitimate in the eyes of the Egyptian government, although two years ago, the Government of Egypt assured the seller, the Borough Council of Northampton, that it had “no right to claim the recovery of the statue.” (CCP).

Egypt’s paradoxical position may have partially informed The Art Council of England’s rebuttal to the auction sale of Sekhemka.

On August 1, 2014 The Arts Council of England released a definitive statement that as a governing body it would be revoking the museum’s credentials until a review in 2019. This decision primarily effects a potential loss in the revenue of arts and grant funding that The Arts Council of England provides access to and awards on behalf of its accredited members.

On the surface, this is an offbeat story about a shoeless statue being sold by a museum mainly known for its shoes. In the final analysis, this story begs the question, “How in challenging economic times do we ensure that ancient works of art will be maintained, cared for and accessible to all?”