Last Things First

Thoughts on Stone Carving, Sculpture, and Aesthetics

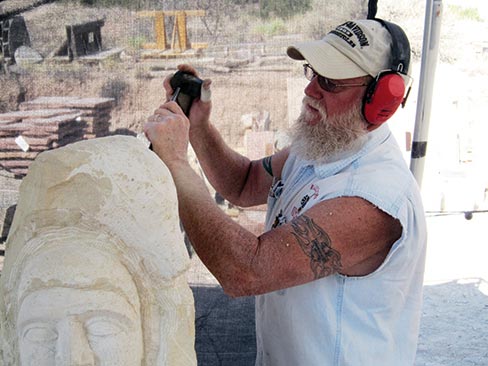

Mark Saxe

Special Contributor

Photos courtesy of Mark Saxe

The purpose of this article is to help aspiring stone carvers and sculptors judge their own work.

The purpose of this article is to help aspiring stone carvers and sculptors judge their own work.

My goal is to set the stage for an ongoing dialogue on the subject of aesthetic considerations. It is a subject which is often overlooked in our fast-paced “just get it done” world.

My goal is to set the stage for an ongoing dialogue on the subject of aesthetic considerations. It is a subject which is often overlooked in our fast-paced “just get it done” world.

Over the last 13 years of organizing our Sax Stonecarving Workshops seven-day intensive sessions, I have noticed that although many participants are eager to delve into this area of inquiry, it hardly gets touched upon during the workshop. After all, it is a difficult topic to discuss, words are hard to find, and there is only so much time for so much technique to be covered. Everyone wants to finish his or her piece.

Over the last 13 years of organizing our Sax Stonecarving Workshops seven-day intensive sessions, I have noticed that although many participants are eager to delve into this area of inquiry, it hardly gets touched upon during the workshop. After all, it is a difficult topic to discuss, words are hard to find, and there is only so much time for so much technique to be covered. Everyone wants to finish his or her piece.

Every carver, every sculptor, wants to give form to an idea. Students come to the stone carving workshop to give form to their idea, to capture an image, dream or story. How successful a work is will be judged, ultimately, by each individual carver and by his or her audience.

Every carver, every sculptor, wants to give form to an idea. Students come to the stone carving workshop to give form to their idea, to capture an image, dream or story. How successful a work is will be judged, ultimately, by each individual carver and by his or her audience.

Every one of the thousands of marks a stone carver makes will count. Each mark represents an aesthetic and practical decision, a step along the path to creation, building on the previous marks until a final form emerges. It is our task as creators to organize all the marks so that the result is a compelling, well-executed object.

Every one of the thousands of marks a stone carver makes will count. Each mark represents an aesthetic and practical decision, a step along the path to creation, building on the previous marks until a final form emerges. It is our task as creators to organize all the marks so that the result is a compelling, well-executed object.

“We can teach you how to carve but not what to carve,” was the opening statement made by guest instructor, Fred X. Brownstein, on the first day during our 13th Annual Sax Stonecarving Workshops in 2013.

“We can teach you how to carve but not what to carve,” was the opening statement made by guest instructor, Fred X. Brownstein, on the first day during our 13th Annual Sax Stonecarving Workshops in 2013.

It was a salvo of sorts, a shot across the bow, a challenge in subtle terms to each student: Think not just about the technique of carving, but consider your concept, your design, your composition, your subject matter. How are you going to use technique as a servant to your idea (rather than as its master) so that the resulting object presents itself as an organized unity which is memorable and exudes confidence? These are difficult questions.

It was a salvo of sorts, a shot across the bow, a challenge in subtle terms to each student: Think not just about the technique of carving, but consider your concept, your design, your composition, your subject matter. How are you going to use technique as a servant to your idea (rather than as its master) so that the resulting object presents itself as an organized unity which is memorable and exudes confidence? These are difficult questions.

Technique, of course, is what participants have come to learn, first and foremost. Without it we are in the proverbial “boat without a paddle.”

Technique, of course, is what participants have come to learn, first and foremost. Without it we are in the proverbial “boat without a paddle.”

At our workshops, we explain and demonstrate all the essential techniques and safety considerations: how to work in a safe manner, the geology of carving stone, tool use and care, how to rough out a piece using hand and power tools, measuring methods, working from a model, rigging, texturing, polishing, pinning and mounting, lettering, repairing, and finally – time permitting – we talk about aesthetics. In many respects, this last subject is the most important, since with every stroke of the hammer, we make an aesthetic decision.

Just as night surely follows day, making good decisions every step of the way will more than likely lead to a successful piece. I have observed over the years that the best finished pieces looked good at every stage of the way. Even in the very rough stages, the beauty was somehow evident. Of course that quality had something to do with the mastery of technique, but a lot of it had to do with paying attention and concentration. At its best the process is a meditation.

If you look at Michelangelo’s slave series, you will see the beauty and intentionality of every mark. Michelangelo could serve as a standard, not to measure ourselves against, which would be daunting, but for lessons about how to approach our own carvings: Know where you’re going with a project, have a clear idea, a plan. And at the same time leave open the possibilities of deviation and change as you progress. Allow technique and vision, technique and thought, technique and spirit, to join forces.

What are the ingredients that make for a good work? What is good form? What is “balance” and why does it matter? How do I achieve that sense of organic unity such that all the shapes, lines, and textures work together like the parts of a well-designed machine, like a team of sled dogs with single-minded purpose, like the way the human body flows from neck to shoulder and shoulder to arm, or like the way the wind creates the shapes we see in the desert dunes? What is necessary? What is unnecessary? How can I tell the difference?

More often than not these questions resolve themselves only after countless hours of hard work. There are no short cuts. There’s no “app” for that. Every piece builds off of the previous one. Practice, practice, practice. We learn from our mistakes.

The first consideration on this journey is the stone itself. Each carver selects a stone, evaluating such practical things as structural feasibility, size, and hardness. Since every material has qualities which are appropriate for certain forms, shapes, and subjects, we should also ask ourselves: How will I allow the material to express its personality? Will I be able to help it come to life? What can and cannot this stone offer?

Next, each student must decide how to place his or her vision in the block of stone. We use measuring tools, rulers, calipers. You don’t want to find out after many hours of carving that there is no stone left for that other ear. The golden rule of carving is explained: Carve from top to bottom, front to back. And the carving begins.

What do you want to say? What emotion are you trying to express? How best to present it? What is it about your project that captured your imagination? Is it the elusive movement of a fish in water, the beauty and elegance of geometry, a narrative piece expressing joy or sorrow, a piece celebrating the grandeur of nature?

Another good rule to follow is to keep things simple. By doing so, we are able to keep track of things and see how shapes begin to relate to one another. We start to consider the more complex issues of balance, variety, rhythm, intent, and composition. When all of these considerations are taken into account and incorporated, the result usually seems to be a work which is both interesting and displays that often elusive quality of organic unity.

There are innumerable carvings and sculptures to look at and study, and hundreds of books dealing with subject. The more you look, the more discerning your eye becomes. What differentiates an ordinary work from an extraordinary work? What stops you in your tracks, takes your breath away?

Of course, there is a lot of subjectivity involved, since everyone brings his or her own history and inclinations to bear. Do you prefer curves over straight lines, colorful stones over dark or monochromatic stones, simple shapes over complicated ones? Ask yourself questions! The more self-knowledge one has, the better the work will be. It is part of developing your own personal aesthetic and style. It makes your work special.

The range of styles is wide open – from the beautiful, primitive sculptures of William Edmondson, the dazzling virtuosity of Bernini, or the truth to material, nature-based sculptures of Isamu Noguchi and Kazutaka Uchida. What is common to each of these great artists is that their work exhibits control, confidence, and authenticity.

Many artists, sculptors and carvers start by mimesis or copying in order to hone their skills, which is a good way to develop your eye and stimulate your imagination. We all have style; cultivating it is a life long task which requires considerable commitment. Find what is unique to you, what is peculiar to your own time and place, what most captures your imagination, what you love. It will show through in your work.

In his book The Quality Instinct, Maxwell Anderson, museum director and curator, lists five qualities that he considers to be essential in evaluating a work of art:

1. Original in approach

2. Crafted with skill

3. Confident in its theme

4. Coherent in composition

5. Memorable to the viewer

Anderson recommends looking at everyday objects – cars, boats, toasters, cups, tools - and applying these criteria to them as a means to developing an eye for quality. What makes that Maserati so captivating and memorable? What makes a good tool better than a cheap one? In each case, the superior object is designed with care, and crafted with great skill. The maker didn’t skimp on materials.

Both the Maserati and the quality tool are well-proportioned and elegant, or in Anderson’s terms, coherent, authentic, memorable, well-crafted. I would suggest observing our work the way we look at ourselves in the mirror while getting dressed for an important occasion.

We want to make a good impression, to project a certain image. Hair just right, shoes shiny, buttons buttoned, colors complimentary, confident in our choice of style, nothing that would ruin the look. We have poured ourselves, so to speak, into a form. In this same way, the artist allows his or her forms to express style and intention. The maker’s desire is to transform a mental image into pure form.

The journey of discovery and the pathways are too numerous to ponder, but as Wolfgang Goethe said, “Everything is simpler than you think, but at the same time more complex than you can imagine.” And as a Renaissance man once said, “There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion.” An admirable work always includes an element of wonder.

Thank you to the folks at Slippery Rock Gazette for providing this forum.

I welcome your comments. Please reply to southweststoneworks@yahoo.com.

14th Annual Sax Stonecarving Workshops

Session 1, July 12-18, 2014: Letter Carving in Stone with Karin Sprague;

Session 2, August 11-17, 2014: Traditional and Contemporary with Guest Instructor Fred X. Brownstein and Guest Artist Kazutaka Uchida.

All levels are welcome.

For more information about our 14th Annual Sax Stonecarving Workshops schedule and our guest instructors, visit the website www.saxstonecarving.com or call 505-579-9179.