Restoration & Maintenance Corner: Porosity and Stain Protection

Bob Murrell

Special Contributor

Photos courtesy of Bob Murrell

Most all natural stone and many ceramic tile products have a porosity factor. Of course, glazes on ceramic tiles (which are mostly glass) for our purposes here, are not porous.

Most all natural stone and many ceramic tile products have a porosity factor. Of course, glazes on ceramic tiles (which are mostly glass) for our purposes here, are not porous.

What this means to us in the stone industry is that some fraction of the materials in question are comprised of air or gas.

What this means to us in the stone industry is that some fraction of the materials in question are comprised of air or gas.

Porosity of a material is generally defined as the total proportion of air space contained within the solid parts of the material. These air spaces are referred to as pores.

Porosity of a material is generally defined as the total proportion of air space contained within the solid parts of the material. These air spaces are referred to as pores.

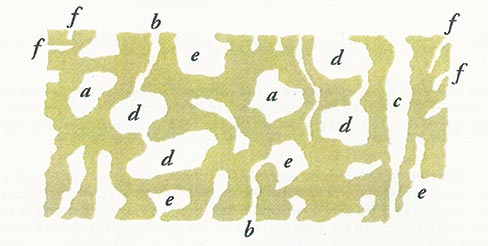

Materials experts can name many types of pores. However, for stone and tile, we can simplify these down to three basic types; open, closed, and interstitial.

Open pores are simply voids that are exposed to the surface,and they occur on the top, bottom and sides of the material. Closed pores are voids or spaces in the material that have no exposure to the surrounding elements. Interstitial pores go all the way through one side of the material to the opposite side, by various internal passageways.

Open pores are simply voids that are exposed to the surface,and they occur on the top, bottom and sides of the material. Closed pores are voids or spaces in the material that have no exposure to the surrounding elements. Interstitial pores go all the way through one side of the material to the opposite side, by various internal passageways.

The open and interstitial pores need protection from penetration of foreign contaminants or staining. This can be accomplished in one of several ways, using sealers, penetrating sealers, or true impregnators.

Sealers are a topical product and provide protection from staining by separating the surface of the material from the potential contaminants with a film-forming polymer. Sealers most always change the natural appearance and can inhibit the natural permeability (ability to transpire water vapor) of the material.

Penetrating Sealers are typically a cross between sealers and impregnators. They usually contain a carrying agent such as some type of solvent or water along with a small amount of polymer or resin. They normally do not leave a topical coating behind. Color enhancing products are generally considered to be penetrating sealers. They don’t affect the permeability quite as much as do the sealers.

True impregnators use either a solvent or water as a carrying agent and some type of fluorinated copolymer (silicone, siloxane, Teflon, etc.). The carrier floods the pores of the material, taking the fluorinated copolymer molecules into the open and interstitial pores.

Once the material is saturated, the carrier evaporates leaving the fluorinated copolymer molecules behind. They attach themselves to the walls of the open and interstitial pores. With quality impregnators, the material may retain up to 90% of the original permeability. Normally, they don’t appreciably affect the natural appearance of the material.

Impregnators work by infusing the fluorinated copolymers into the material. These molecules repel liquid foreign contaminants by setting up an electrostatic barrier. The contaminants are then repelled much the same way one north pole of a magnet is repelled by the north pole of another magnet.

Impregnators can offer either hydrophobic (water) or oleophobic (oil) protection. Higher quality impregnators are oleophobic meaning they resist grease, oil, and water borne materials. Hydrophobic resists only water borne contaminants.

Impregnators can’t give a 100% staining protection but will get very close. Most contaminants will evaporate before penetrating a well impregnated surface. Acids are another issue. On acid sensitive materials like marble and limestone, impregnators can only keep the acid from penetrating deeply but will not stop the surface from etching. However, the impregnator does keep the etching closer to the surface allowing for much easier re-polishing.

It is my opinion, and feel free to make it yours too, that most natural stone and masonry surfaces will benefit from some sort of stain protection. Polished granite countertops can certainly be stained by olive oil or grease splatter from cooking. Marble can also stain from various contaminants.

Textured stones like tumbled marble, flamed granite, slates, quartzites, sandstones, and like materials, can be protected and are often better appreciated when color enhanced or even sealed with a topical coating for added color and shine. By the way, some granites are more porous than many marbles, and vice versa.

All of these products will help protect the stone’s surface to some degree. Which product/process is best for your particular application must be considered and confirmed with the customer. Submitting test pieces for approval is highly recommended when possible.

How long do sealers, color enhancers, and impregnators last? Well, there are many variables that come into play. Foot traffic, exposure to UV, wind, rain, sand, and the elements are all factors. Maintenance practices also can affect the life of these products.

I have read some company impregnator advertisements that say they guarantee their product for 20 years. I would agree with that, but only if the product is applied to an interior vertical surface with no wear factors. However, exterior surfaces and heavy traffic areas do not apply to this assumption.

As we have discussed in previous articles, foot traffic has a wear abrasion factor of between 200 grit and 400 grit. Applying this to the pore structure of a natural stone surface, previously open pores that received impregnator may be worn away.

Previously closed pores that never received impregnator may now be come exposed. So you see, impregnator life is mostly determined by wear and maintenance.

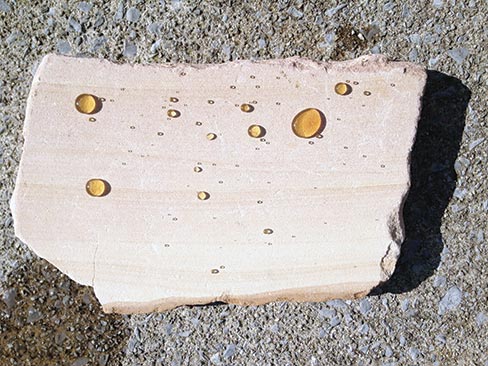

Impregnator integrity testing is not very complex. Simply pour some water on the surface. If it repels the water satisfactorily for a decent period of time, the impregnator is still working as intended. If the material absorbs the water too quickly, it is time to reapply.

It should be obvious whether sealers need repair or replacement as they will be abraded or removed by wear, fade from excessive weather exposure, or possibly even cloud up due to vapor entrapment.

Some color enhancers will eventually fade, especially when exposed to UV. Normally the surface can be cleaned and the product simply reapplied. The notable exception to UV fading is Stone Shield Color Enhancer & Sealer.

Of course, if the material is protected from staining, any staining that does occur will be much easier to remove either by cleaning or use of a poultice.

I suggest that you always consult with a reputable distributor and solicit their input as well as the customer’s expectations. Ultimately, the customer will depend upon your recommendations.

Bob Murrell has worked as a supplier of products and technical support to the natural stone industry for over 35 years. He has written numerous articles for various trade publications and has also trained thousands of contractors over the last 25 years.